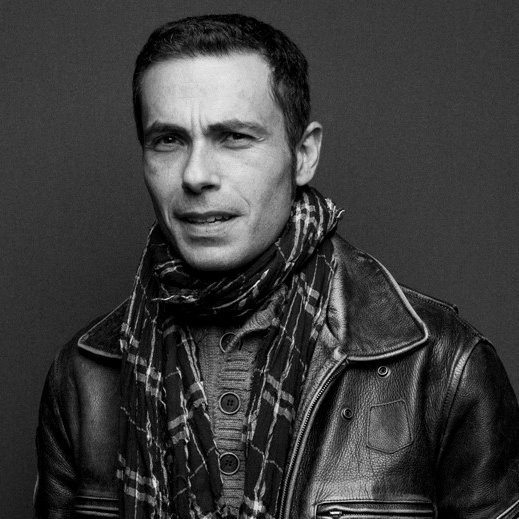

Who is Leonardo Valenti?

I am primarily a television screenwriter, an executive producer, and since 2024 also Head of Drama for generalist projects at IIF, one of the oldest film and television production companies in Italy.

I began writing professionally in the early 2000s and my name is attached to some of the biggest Italian TV successes, such as Distretto di Polizia, RIS (which had three European remakes), and Romanzo Criminale – The Series.

For cinema, I helped launch the careers of directors like Stefano Sollima, writing the script for ACAB, and Edoardo De Angelis with Mozzarella Stories. I was also a comic book writer, which was my very first love, but for now I have put it aside to focus on television work.

Do you remember the exact moment you fell in love with cinema?

There is a moment I will remember forever, and it was my encounter with the cinema of Steven Spielberg. Raiders of the Lost Ark was the first film I explicitly asked my parents to take me to see. Until then, they chose the movies; that time, I chose.

Before that, I wasn’t interested in who made films, I didn’t know directors’ names. From that moment on, everything changed. Spielberg became a reference point, also because that historical period was shaped by the aesthetics of his Amblin and of Lucasfilm.

It was a shock to discover, with The Color Purple, that Spielberg didn’t only tell beautiful fairy tales and that cinema could also be something else. Ultimately, I was nurtured and weaned by Spielberg: a talent and an idea of cinema that are probably unrepeatable.

Tell us about your project “TV Man – Te L(e)o Comando”.

TV Man – Te L(e)o Comando is the first fully realized short film I directed back in 1997. It disappeared into nothingness for twenty-eight years and then, out of nowhere, resurfaced in 2025.

I had already made short films before, but they were fragments, without real narrative development. With this one, I challenged myself for the first time with a “structured” story: setup, first turning point, second act, midpoint, second turning point, climax… and epilogue.

In the 1990s, for a kid from a small town, it was very difficult to find someone willing to produce a short film (especially one like TV Man). But the ’90s were also the era when talents like Robert Rodriguez, Kevin Smith, and Richard Linklater emerged—people who picked up a camera without asking anyone for money and, with a few thousand dollars scraped together personally, produced their debuts.

I didn’t have a few thousand euros; I had a few hundred. But I was inspired by the DIY ethic to make my short film. No crew—just me and the actors, who were friends—four locations, all shot on S-VHS, which was the only recording medium I had. Editing and sound design were also DIY: two VCRs and an audio mixer.

The result was a small miracle that, twenty-eight years ago, no one saw and that vanished into thin air. Today, thanks to my sheer nerve in sending it around without shame, it has been selected by over 60 festivals, received 10 honorable mentions and 8 awards—and it hasn’t finished its run yet.

TV Man is naive, imperfect, innocent, but it has something that reaches the four corners of the globe.

Which director inspires you the most?

Today, I am especially inspired by Eastern directors, particularly Japanese filmmakers, who culturally manage to keep in check the logic that has devoured and killed our sense of wonder, and who are capable of a meditative calm that we no longer seem able to find.

That said, my favorite directors are many: from Spielberg to Scorsese, passing through David Lynch, John Woo, Chuck Jones, and Isao Takahata. I don’t have recent reference directors because I find most contemporary cinema derivative. I don’t need to see “a new version” of something I already know—I prefer going back to the source.

What do you dislike about the world, and what would you change?

Hypocrisy, cynicism, fear of others, cruelty. We are dehumanizing ourselves without realizing that the solution is to connect, to build networks.

We had arrived at this great dream toward the end of the 1980s, with the fall of the Berlin Wall: the dream of a global world, of a united Europe. That dream was destroyed, while making us believe that there are no alternatives to cruelty and reciprocal violence.

That is not true. I wish someone would help people recover faith in a great shared project—something we are missing today. Because only a great common project can allow us to look at the future with hope. Today, they have taken the future away from us. They have taken hope away from us.

How do you imagine cinema in 100 years?

I have to be realistic. New forms of AI push me to think that, in 100 years, movie theaters may no longer exist, and each of us will be able to create our own personal film at home using prompts. This will globally lead to the collapse of traditional production systems.

Human originality, however, will still manage to assert itself, because only the most powerful, original works—those with a true voice—will be able to leave living rooms and reach a wider audience.

But it will be a self-sufficient genius, who won’t need huge budgets and will generate very high profits. Just think that today an application like Suno can already create music tracks from scratch using prompts and roughly hummed melodies. How long will it take before an artist born with Suno becomes a massive commercial success? Not long, I’m sure. From there to a film produced entirely at home, the step is very short.

What is your impression of WILD FILMMAKER?

I only know WILD FILMMAKER superficially, but it seems like a dynamic and extremely interesting initiative. I love its philosophy and I am impressed by the visibility results it has achieved. I’m very happy to have taken part in this interview for you.