By Michele Diomà

Alejandro Jodorowsky once said: “When you doubt between acting or staying still, choose the desire to act – create your path, one step at a time.”

Inspired by this quote from the great Chilean poet and filmmaker, WILD FILMMAKER was born five years ago with the mission to give visibility to independent artists around the world.

In the beginning, WILD FILMMAKER was just a magazine, but my dream was to create a platform where filmmakers and screenwriters could participate in events judged by one single criterion: MERITOCRACY.

I never imagined that this revolutionary dream would bring me, in June 2025, to San Francisco and Silicon Valley, to organize two events that saw a record-breaking turnout of over 35,000 independent artists from across the globe.

(San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge)

Reaching California—the heart of both the past and present film industry—and becoming the leading platform for indie cinema is an unprecedented victory for the entire WILD FILMMAKER community.

When I say “past and present,” I mean that California is home to both Hollywood and Netflix. WILD FILMMAKER positions itself somewhere in between these two worlds: with the mission to use the classic cinematic storytelling style—yet through the web.

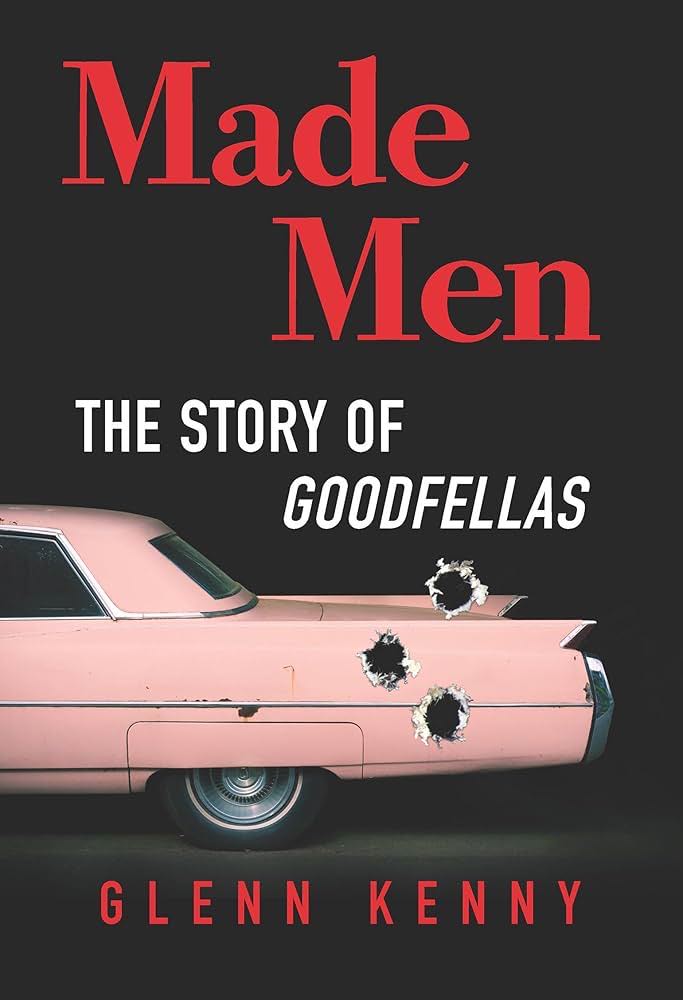

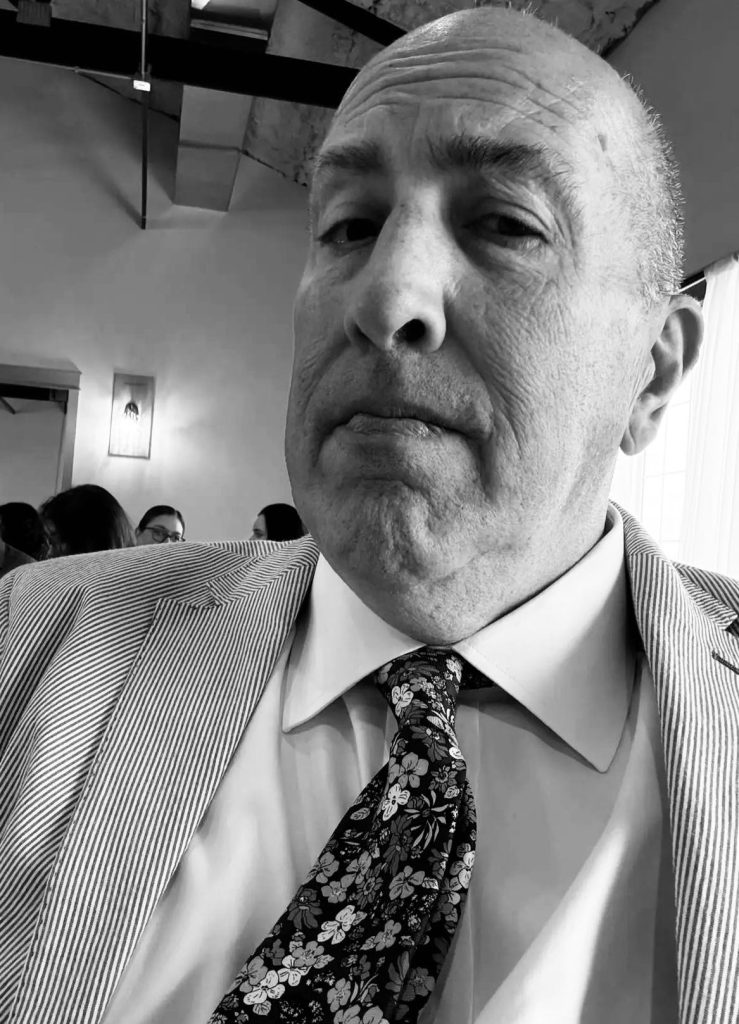

Today, WILD FILMMAKER is the most globally recognized independent film brand. Just a few days ago, we hosted The New York Times on our pages with an exclusive interview with Glenn Kenny, one of their top film critics. Over the past year, we’ve also appeared in Vogue, The Hollywood Reporter, Variety, and Cinecittà News.

(Academy Award winner Martin Scorsese alongside New York Times film critic Glenn Kenny)

This victory is dedicated to all those who believed—and continue to believe—in the WILD FILMMAKER project.

Our mission is not to ask permission to enter the traditional film circuit, but to create a new way to tell and distribute cinema, and we’re making it happen!

A special thank you to the artists who participated in this PRESS RELEASE dedicated to the San Francisco Film Achievement Awards:

Lesley Ann Albiston – Fractures In Time

BEST ARTHOUSE FEATURE SCRIPT 2025 & BEST ORIGINAL IDEA

Janja Rakuš – Soularis

BEST INTERNATIONAL EXPERIMENTAL SHORT FILM 2025 & BEST EUROPEAN DIRECTOR

Emilio Mercanti – Tic Tac

BEST EUROPEAN NARRATIVE SHORT & BEST INTERNATIONAL FILMMAKER & BEST SCREENPLAY SHORT (Category: Arthouse Short Film)

Roger Paradiso – The Lost Village

BEST AMERICAN PRODUCER & BEST INDIE DIRECTOR

Hugo Teugels – Cassandra Venice

BEST INTERNATIONAL ARTHOUSE FILMMAKER & BEST EUROPEAN PRODUCER

Monte Albers de Leon – Mecca

BEST LGBTQ SCRIPT 2025 & BEST AMERICAN ORIGINAL SCREENWRITER

AnayaMusic Kunst – Sanctuary

BEST MUSIC VIDEO 2025 & BEST ARTHOUSE SINGER

Jamie Sutliff – Black Wolf

BEST FILMMAKER & BEST SCREENWRITER (Category: Indie Short Film)

Mattia Paone – Flashes of Light (Bagliori)

BEST EUROPEAN SCREENPLAY 2025 (Category: Narrative Short), BEST ORIGINAL INDIE DIRECTOR & BEST EUROPEAN CINEMATOGRAPHER

Vicentini Gomez – Doctor Hypotheses 2 – The Breakdown

BEST INTERNATIONAL COMEDY SCRIPT 2025 & BEST SCREENWRITER (Category: Comedy)

Andronica Marquis – Medea

BEST INTERNATIONAL DIRECTOR (Category: Narrative Short), BEST SCREENPLAY SHORT, BEST CAST, BEST ORIGINAL EDITING & BEST CASTING DIRECTOR

Chris Ross Leong – NeverWere: a Lycan Love Story

BEST ORIGINAL FEATURE SCRIPT & BEST INTERNATIONAL ARTHOUSE WRITER 2025

Jonathan Fisher – In a Whole New Way

BEST SOCIAL SCREENPLAY, BEST HUMAN RIGHTS PROJECT & BEST EDUCATIONAL FILM 2025

Carla Di Bonito – Nossos Caminhos (Our Paths)

BEST ORIGINAL SCREENPLAY & BEST INTERNATIONAL WRITING STYLE

Michał Kucharski – Heat and Love

BEST ANIMATED SHORT FILM 2025, BEST FILMMAKER & BEST ARTHOUSE PRODUCER

C. Arnold Curry – The Duchess

BEST AMERICAN SCREENPLAY 2025 & BEST INTERNATIONAL DRAMA

Susan Downs – Something Ain’t Right

BEST DIRECTOR & BEST ORIGINAL DOCUMENTARY 2025

Christopher Pennington – Virulence

BEST ARTHOUSE SCREENWRITER & BEST INTERNATIONAL INDIE FEATURE SCRIPT

Pamela PerryGoulardt – The Girl Made of Earth and Water

BEST SUPER SHORT FILM, BEST EDITING & BEST FILMMAKER

Dean Morgan – Sheldon Mashugana Gets Stooged

BEST AMERICAN ACTOR 2025 & BEST SCREENPLAY (Category: Comedy)

Kai Fischer – Lambada The Dance Of Fate

BEST BIOGRAPHICAL SCRIPT & BEST EUROPEAN SCREENWRITER 2025

John Martinez – The Days of Knight: Chapter 1

BEST AMERICAN NARRATIVE SHORT 2025, BEST CINEMATOGRAPHER, BEST INDIE DIRECTOR, BEST CASTING DIRECTOR & BEST PRODUCTION COMPANY.

R.Scott MacLeay – Noise

BEST DIRECTOR, BEST EDITING & BEST ORIGINAL CINEMATOGRAPHY (Category: Experimental Film)

Don Pasquale Ferone – Credo

BEST SONG 2025, BEST EUROPEAN SONG WRITER & BEST SPIRITUAL MUSIC VIDEO

Russell Emanuel – Routine

BEST DIRECTOR 2025, BEST PRODUCER, BEST ORIGINAL IDEA & BEST NARRATIVE SHORT 2025

– The Assassin’s Apprentice 2: Silbadores of the Canary Islands

BEST INTERNATIONAL ARTHOUSE SHORT FILM, BEST DIRECTOR, BEST SCREENPLAY SHORT & BEST ACTING (Category: International Indie Narrative Short Film)

Brooke Wolff – Eye of the Storm

BEST BIOGRAPHICAL DOCUMENTARY 2025, BEST DIRECTOR, BEST PRODUCER, BEST STORYTTELING & BEST ORIGINAL EDITING (Category: Documentary Feature)

Lena Mattsson – Not Without Gloves

BEST POETRY FILM, BEST FILMMAKER & BEST CAMERA OPERATOR (Category: Experimental)

– The Rorschach Test

BEST INTERNATIONAL EXPERIMENTAL FILM & BEST SOUND DESIGN

Vincenzo Amoruso – The Arcangel Of Death

BEST EUROPEAN ACTOR 2025 & BEST EXPERIMENTAL CINEMATOGRAPHY (Category: Indie Short Film)

Lynn Elliott – Ghost Town, N.M.

BEST AMERICAN FEATURE SCRIPT 2025

– Alta California

BEST WRITING STYLE (Category: Feature Script)

– Borderline Justice

BEST ORIGINAL FEATURE SCRIPT & BEST INTERNATIONAL INDIE SCREENWRITER

Larry Gene Fortin – The Call Center

BEST INTERNATIONAL TELEVISION SCRIPT & BEST PILOT TV

– Sky Walker

BEST INTERNATIONAL DRAMA SCRIPT 2025

Sean Gregory Tansey – The Stones of Rome

BEST ARTHOUSE ACTOR, BEST INDIE EXPERIMENTAL SHORT FILM & BEST ORIGINAL EDITING

– The Pathos of Hamlet

BEST HISTORICAL SHORT FILM & BEST ACTING

Suzanne Lutas – The Dead Ringer

BEST WRITER OF THE YEAR (Category: Original Feature Script)

Uniqueness Heiress & Azia – Omnipotent Resolution

BEST ARTHOUSE SHORT FILM, BEST SOUNDTRACK, BEST SOUND DESIGN, BEST INDIE MUSICAL & BEST INTERNATIONAL CHOREOGRAPHY

Phoebe von Satis – Hummel

BEST INTERNATIONAL SHORT SCRIPT 2025, BEST WRITING STYLE & BEST AMERICAN SCREENWRITER

– K Bender (The Bloody Benders)

BEST ARTHOUSE SCREENWRITER OF THE YEAR

– The Insomnia Experiment

BEST ORIGINAL WRITER OF THE YEAR (Category: Short Script)

– The Hallmark Couple

BEST ARTHOUSE FEATURE SCRIPT & BEST ORIGINAL IDEA

– Only in Malibu

BEST AMERICAN FEATURE SCRIPT 2025

– Gold, Glory & Nobility

BEST INTERNATIONAL BOOK 2025

Ugrin Vuckovic – Fishbowl

BEST INDIE SUPER SHORT FILM 2025