By Michele Diomà

Today WILD FILMMAKER will have the immense privilege of publishing an exclusive interview with Father Antonio Spadaro regarding the first draft of the screenplay of the new film about Jesus that Martin Scorsese is currently developing. It is a gift offered to the Global Movement dedicated to the promotion of indie cinema, WILD FILMMAKER, and one that makes me particularly happy, especially since the Oscar-winning Italian-American director has stated that it will be a low-budget, black-and-white film, a project that promises to be a true return to Scorsese’s roots as an indie filmmaker.

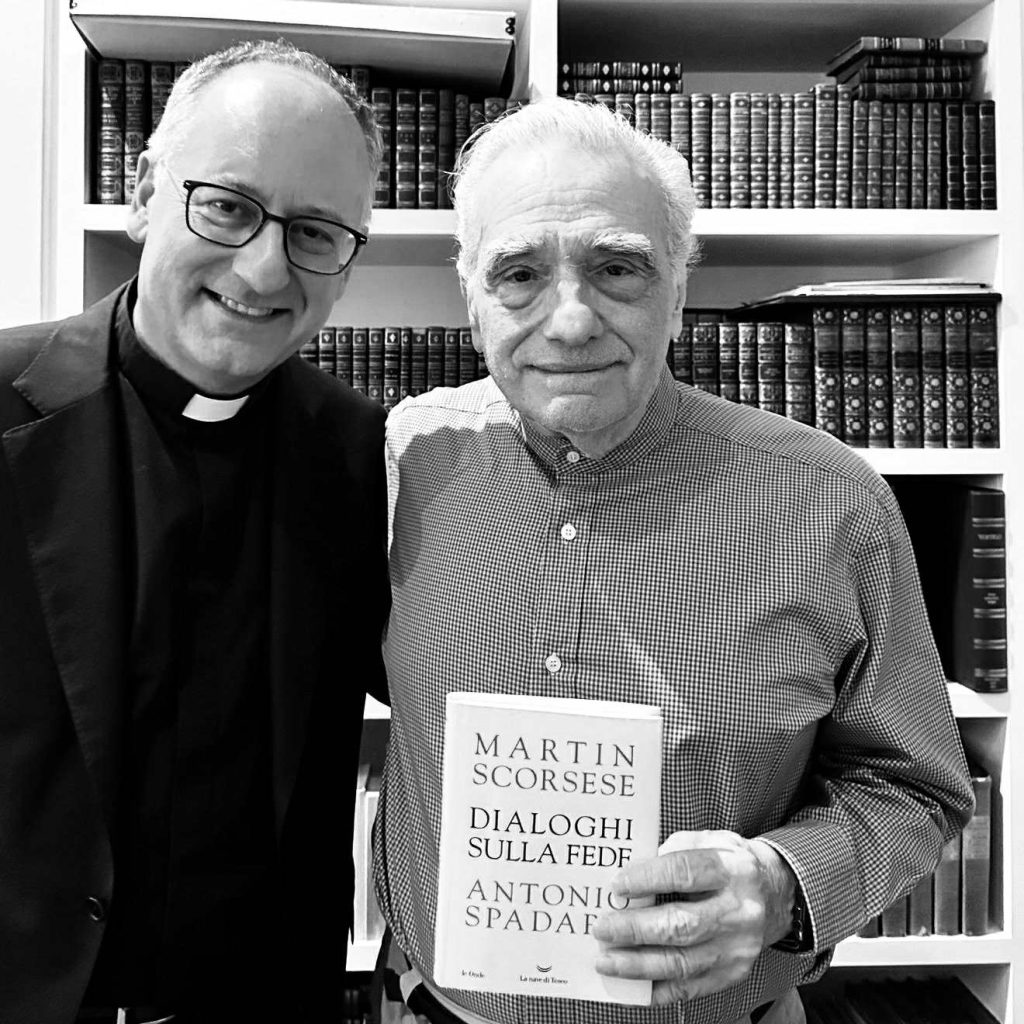

Thanks to Father Antonio Spadaro, already co-author with Martin Scorsese of the book Conversations on Faith, today WILD FILMMAKER makes a dream come true.

What are the differences between the 1988 film The Last Temptation of Christ and Martin Scorsese’s new screenplay devoted to the figure of Jesus?

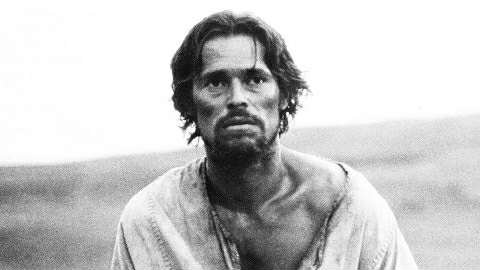

The Last Temptation of Christ (1988) is a traditional narrative film set in the first century, based on the novel by Nikos Kazantzakis, which imagines an “alternative life” of Jesus, including the “temptation” to come down from the cross and live a normal life. Scorsese’s new screenplay about Jesus, by contrast, takes a very different form: it is not a linear retelling of Christ’s life, but rather a mosaic of largely contemporary scenes interspersed with historical segments, which, according to Scorsese, “would not be a linear narrative… but a combination of things.” In fact, the director himself is expected to appear in the film as a narrator or witness, pointing to a meta-cinematic approach. This fragmented and reflective structure contrasts with the unified narrative flow of The Last Temptation. Moreover, while the 1988 film followed Jesus’ life chronologically, emphasizing his human-divine inner conflict, the new work is “partly set in the present day, partly in antiquity” and weaves in modern scenes to make Jesus’ message more immediate and relevant. In 1988, Scorsese aimed to present a deeply human and compassionate Jesus, someone approachable even by the most desperate sinner. As he himself said, he wanted the Christ of The Last Temptation to be “the compassionate Jesus that a poor drug addict on his deathbed… might encounter,” a Messiah who rejects no one. However, that film also emphasized Jesus’ inner struggles, doubts, and even earthly temptations, elements that led some religious groups to accuse it of blasphemy.

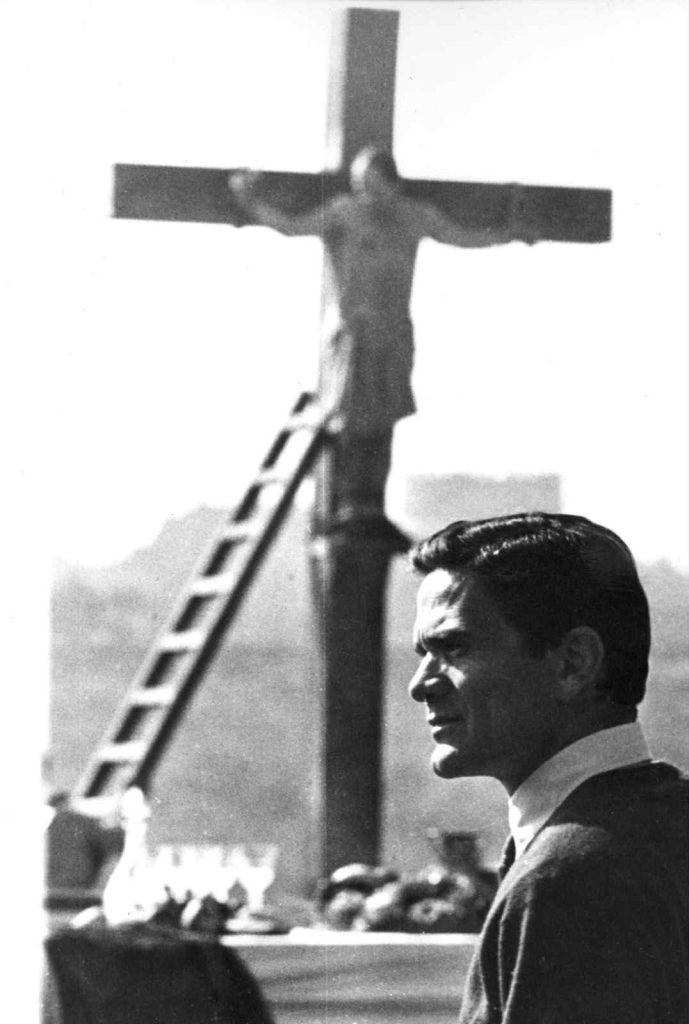

The new screenplay focuses less on Christ’s personal temptations and more on his core teachings and their relevance today. Scorsese has described it as concentrating on the “basic principles” of Jesus, without any intent to preach. In other words, while The Last Temptation explored the conflict between Christ’s human and divine natures in a dramatic way, the new work aims to reveal the heart of Jesus’ message,love, compassion, forgiveness, stripping it of the encrustations of centuries. Scorsese has explicitly said: “I’m trying to find a new way [to represent Jesus] that makes him more accessible, removing the negative connotation associated with organized religion.” This intention marks a significant tonal difference from the 1988 film, which challenged viewers with a visceral and potentially divisive portrayal of Christ. The Last Temptation of Christ was shot in the late 1980s with a modest budget for the time (about $7 million), but still with the backing of a Hollywood studio, filmed in exotic locations (Morocco) and in color. The new screenplay, provisionally titled A Life of Jesus, will be made deliberately on a very low budget and as an independent production. Scorsese has stated that it will be one of his least expensive projects in decades, signaling a return to a more intimate style of filmmaking. He has also revealed that he intends to shoot it “almost certainly in black and white”—an aesthetic choice that sharply distinguishes it from the warm-toned cinematography of The Last Temptation. This decision recalls an old dream of the young Scorsese: in the 1960s, inspired by Pasolini, he imagined filming the life of Christ in 16mm and in black and white. Now, after 25 years of making high-budget films, he seems determined to recapture that spirit, giving up color and lavish production values in favor of a more essential approach. In summary, The Last Temptation represented for Scorsese a long and troubled attempt to “find a new vision” of Jesus through the lens of a literary novel, whereas the new screenplay is a meditative and autobiographical experiment that combines contemporary images and spiritual reflection, aiming to speak directly and simply to today’s world.

Martin Scorsese is a versatile director in the way only Stanley Kubrick knew how to be; yet, despite the differences in genre from one film to another, a deep spirituality is always present in the characters of Scorsese’s filmography, even in the negative ones. What are the characteristics of the character of Jesus in the new screenplay?

In the new screenplay, the “character” of Jesus emerges in an unusual way: he is not a flesh-and-blood protagonist who acts scene by scene, as in traditional films, but is present as a living spirit and an active principle within the narrative. Spiritually, Jesus is described as omnipresent in human love. A voice-over states clearly that “Jesus contains multitudes. He is constant. He is present in every gesture in which we are moved to act out of love.” This line underscores a vision of an immanent Christ: Christ is there every time someone performs an act of genuine, selfless love. It is not love limited to a person or a thing, but rather “love as a source of power,” universal in scope. From a spiritual point of view, then, Jesus is portrayed as the Logos of love that permeates the world—an image that is strongly positive and inclusive, in line with the theology of Shūsaku Endō. Indeed, Endō, the Japanese Catholic author on whom the film is based, portrayed Jesus as an almost “maternal” figure in his mercy: one who “suffers with us” and forgives our weakness, more like a loving mother than an inflexible judge. This sensibility is reflected in Scorsese’s text: his Jesus is not so much a stern lawgiver as the face of God’s compassion, always in solidarity with suffering humanity. From a psychological point of view, the screenplay highlights the way Jesus touches people’s conscience and hearts. He is described as the one who challenges human beings to look beyond their fears and habits. A famous saying of Jesus is cited, for example: “I did not come to bring peace, but a sword” (Matthew 10). The voice-over asks rhetorically: does Jesus perhaps incite violence? And it immediately answers: “Of course not. I believe instead that it is an invitation to look through every doubt and to seek God within ourselves, that authentic feeling that moves us to act out of love.” Here we see the “psychological edge” given to the figure of Christ: Jesus’ “sword” is interpreted as a salutary crisis, a clean cut that forces a person out of apathy or convention. In the screenplay this is translated into an emblematic scene: a young woman on the subway finds herself confronted by an aggressive homeless man asking for alms. At first she is paralyzed by petty hesitations (“If I have to rummage through ten- and twenty-dollar bills to find one dollar for him, what will others think?…”). But then something extraordinary happens: “She lifts her gaze from her phone and looks directly into his eyes… and he looks into hers. We stay on them, inside that exchange.” In that instant of silence, a revelation occurs: the voice-over comments that when you truly see the other and recognize his humanity, there is the sword of Jesus cutting away all ties to habits, excuses, and conventions, and going “straight to the heart of love.” Psychologically, then, Jesus is portrayed as the one who unsettles and converts hearts, breaking the “safe distance” we keep from others in order to make us experience real empathy. We do not see Jesus tormenting himself as a character in his own right (as happened in The Last Temptation, where we witnessed his inner doubts), but rather we see him reflected in the eyes of ordinary people who, thanks to him, overcome their fears and reach a state of compassion and inner truth. Narratively, this representation of Jesus translates into the absence of conventional scenes from Christ’s life in the first part of the work, in favor of everyday situations with a universal flavor. The screenplay does not show Jesus preaching in Galilee or performing miracles in a realistic way; instead, it actualizes his teachings through visual analogies and allusions. For example, the subway episode is itself a modern “parable-story” about the Good Samaritan or about recognizing Christ in one’s neighbor. Only toward the end, it seems, does Jesus appear indirectly in the form of an iconographic image: Scorsese describes his visit to a monastery on Mount Sinai, where he is struck by an ancient sixth-century icon of Christ Pantocrator, whose penetrating gaze prompts in him the ultimate question: “What does Christ want from us?” In that finale, Jesus appears as a silent and mysterious face that questions the soul. Narratively, then, the “character” of Jesus is present as a living idea rather than as a speaking protagonist: he is the thread that binds all the scenes together (from the homeless man on the subway to the mosaic of quoted film clips), he is the Voice that calls from the depths more than a physical body on screen. This unusual narrative choice, punctuated by quotations from the Gospels and images of sacred art—underscores the spiritual traits of Jesus (constant presence of love, source of ultimate questions) and offers a psychological portrait of Christ through his impact on others (rather than through his own introspection). In short, the Jesus of the new screenplay is ubiquitous and multifaceted (“he contains multitudes”), merciful and compassionate (he suffers with the weak, forgives human failings), and radical in provoking conversion (the “sword” that breaks inner chains). He is less a “historical character” and more a vital, present principle, narratively innovative, yet theologically rooted in the idea of Christ’s presence “in every smallest spark of love” in the world.

I greatly admired your book written in collaboration with Martin Scorsese, Conversations on Faith. Are there points in common between your book and the screenplay devoted to the new film about Jesus?

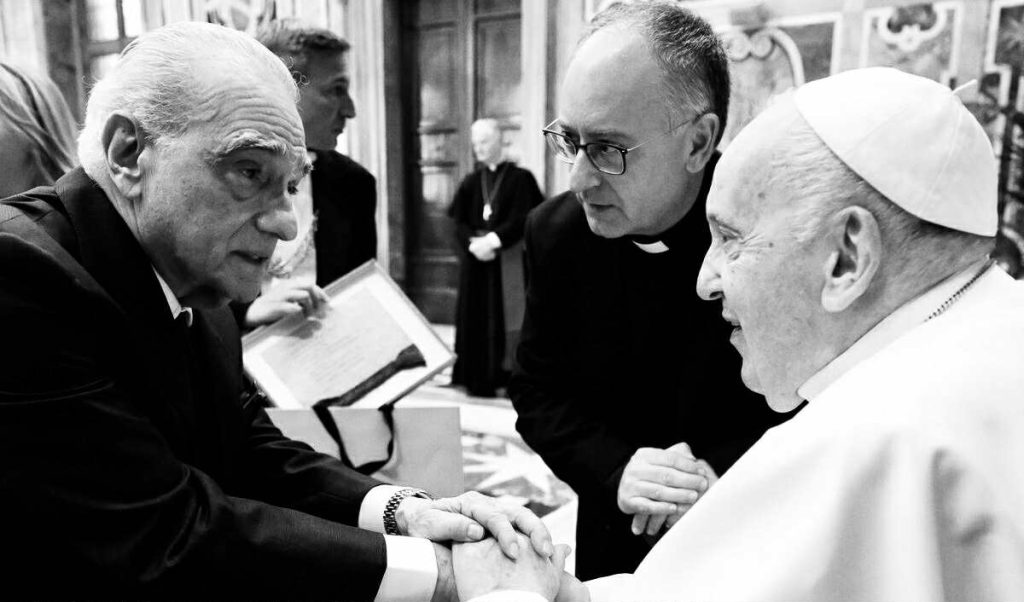

The book Conversations on Faith, the result of my meetings with Scorsese, and the new screenplay share many thematic and expressive turning points, a sign that they spring from the same long interior conversation of Scorsese about faith. A first fundamental theme is the tension between faith and everyday reality, that is, the search for the sacred within the profane world. In the book, Scorsese recalls a childhood memory: as an altar boy, after Mass, he would go out into the street and ask himself in anguish, “How is it possible that life goes on as if nothing had happened? Why isn’t the world shaken by the body and blood of Christ?” I emphasize this “piercing question of a boy who, leaving Mass, wonders why the world has not changed,” a question that in fact has run through the director’s entire spiritual life. The same question is palpable in the screenplay: in the epilogue at the monastery, before the icon, Scorsese, in the first person, feels Christ directly asking him, “But you, who do you say that I am? … What does Christ want from us?”, leaving us with “this fundamental question.” It is the same crisis between the event of faith and the apparent indifference of the world that tormented the young Scorsese. Thus, the motif of a faith that does not leave the world unchanged runs through both the written dialogue and the film screenplay. Both, in fact, do not offer a simplistic answer, but instead relaunch the question toward the reader/viewer. A second point in common is the centrality of grace as it manifests itself among the last and in ordinary situations. In my conversations with Scorsese it emerges how, in many of his films, “grace bursts into the devil’s territory”, to quote Flannery O’Connor, that is, into the most violent or degraded contexts. I note that in much cinema (including Scorsese’s) “a life that appears insignificant can become a place of revelation, and welcoming the weakest is not an optional moral theme but the true center of the story.” This idea, expressed in the book, finds literal confirmation in the screenplay: the subway scene shows an entirely ordinary everyday situation (an ordinary girl, an ordinary subway car) transformed into a place of revelation when that exchange of glances with the homeless man occurs. That man “who counts for nothing” becomes the mediator of an experience of the divine, just like the “poor Christs” in cinema (one thinks of Fellini’s La strada, with its “simple ones” who reveal the meaning of the story, cited in the dialogue). Both Conversations on Faith and the screenplay insist on the Gospel of the small and the lost: in the book, films such as Open City, Umberto D., and Gran Torino are cited, where holiness emerges by sharing the destiny of the most exposed. In the film screenplay, similarly, Jesus is recognized in people on the margins—the drug addict in overdose mentioned by Scorsese in connection with The Last Temptation, or the bothersome beggar on the subway. In both works, narrative and book alike, there is therefore this preferential option for the last as a privileged place of encounter with God. A third shared element is the dialogical, questioning, never doctrinal nature of both the book and the screenplay. Conversations on Faith is, by the authors’ own admission, “the faithful account of a friendship in which faith, grace, and cinema have continually questioned one another.” It is not a treatise of systematic theology, but a series of mutual questions, open explorations. In the same way, the screenplay is not a “thesis film” that aims to provide ready-made answers. On the contrary, it embraces the form of open mystery: Scorsese edits together fragments, cites other directors, shows pieces of stories—from Bresson’s Diary of a Country Priest to his own Silence—and confesses, “We strive to find endings for our stories that give shape to life as we all live it… Staggering forward, I realize that I may be creating images that lead to further questions, further mysteries.” This poetics of asking without exhausting the mystery is exactly what I discuss when commenting on Scorsese’s films: I recall a distinction dear to the director between “a problem and a mystery: a problem has a solution that exhausts it; a mystery never does.” In the Dialogues it is emphasized how Scorsese’s characters often live in a state of insoluble moral conflict, which also involves the viewer in questions without easy answers. The new screenplay, far from preaching or concluding with a single, unequivocal message, in fact ends with an open question: “What does Christ want from us?” And throughout its development it invites reflection rather than the deduction of a single moral. Book and film thus share a contemplative and interrogative approach to faith. Finally, at the expressive level, there is a strong cinephile interweaving in both works. In our Dialogues, we often discuss other films and directors (Pasolini, Rossellini, Fellini, etc.) to express spiritual concepts. Similarly, the screenplay is steeped in cinematic references: Scorsese inserts clips from Le Père Serge (Tolstoy’s “holy fool”), from Bresson, from Europa ’51, and even from his own films such as Silence, The Irishman, Mean Streets, Bringing Out the Dead, Raging Bull, and Casino. This cinematic metalanguage is present both in the written dialogue (where cinema becomes an integral part of the discourse on faith) and in the screenplay (where cinema becomes the very form of meditation on Jesus). In both cases, cinema is seen as a spiritual context: in the book Scorsese says that making a film for him “is like a prayer… an exploration of the soul.” The screenplay is, in effect, a cinematic prayer, where editing and images serve to seek the presence of God in the mosaic of reality. In sum, Conversations on Faith and the new screenplay are united by the same thematic cores: faith as a living search (not a static dogma), the presence of Christ among the poor and the doubting, the surprising grace that can emerge anywhere (in the violent streets so dear to Scorsese since the days of Mean Streets), and a strong awareness that the mystery of God must be told with a new, bold language, including the language of cinema.

Convesations on Faith: https://www.hachettebookgroup.com/titles/martin-scorsese/conversations-on-faith/9781538775387/?lens=grand-central-publishing

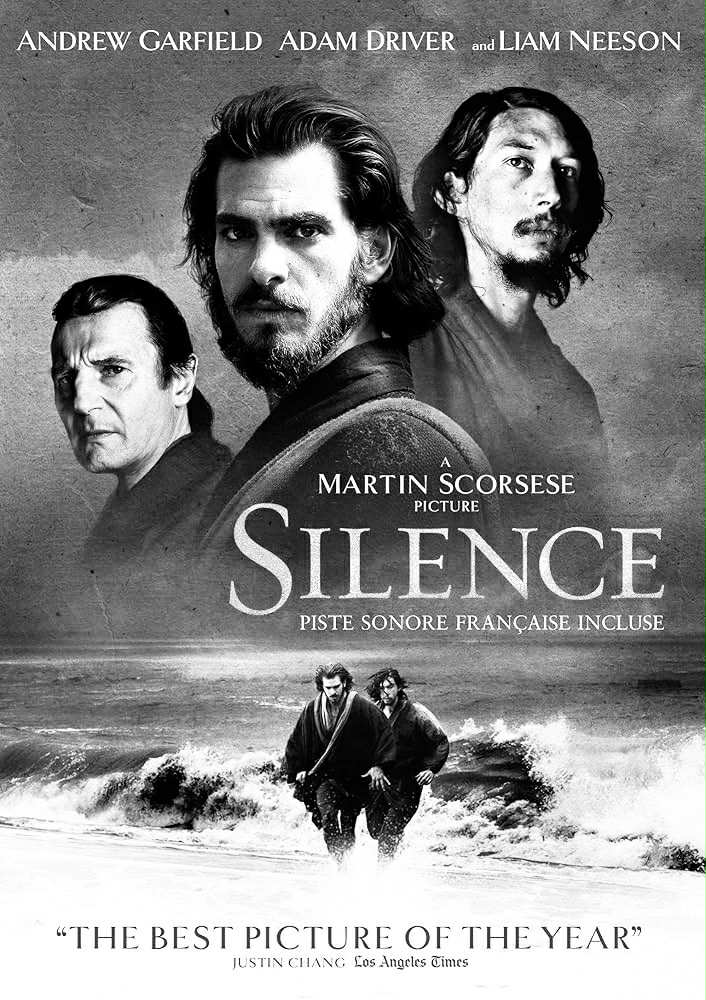

In the beautiful and Bergman-esque Silence (2016), Martin Scorsese confronts the theme of courage and the strength of will that faith in God may require under certain circumstances in which life brings extreme suffering. Can the screenplay of the new film about Jesus be considered a continuation of the reflections already explored in Silence?

The connection between the new screenplay about Jesus and Silence (2016) is profound, almost organic: it can be said that the new project arises as a conceptual and spiritual continuation of the path begun with Silence. First of all, both works are born of the imagination of Shūsaku Endō. Silence was the adaptation of his most famous novel, while the new screenplay explicitly declares that it is based on A Life of Jesus, a 1973 essay in which Endō reinterpreted the figure of Christ. This means that Endō’s same perspective on faith in suffering permeates both works. As a Japanese Catholic, Endō sees in Jesus the God who “suffers with us,” the merciful God who does not break the bruised reed—a Christ with a “maternal face,” capable of infinite compassion. In Silence, this idea was manifested in the climactic scene in which Father Rodrigues, forced to apostatize by trampling on the image of Christ, finally hears the voice of Jesus whispering to him: “Trample! I am with you in this pain.” Scorsese explained that in that moment “Jesus accepts even this humiliation… to lead Rodrigues to a deeper understanding of the mystery of divine love.” Thus, Silence subverts the traditional concept of fidelity to God: true Christian love there consists in becoming a sinner (an apostate) in order to save others—a paradox that reveals Christ’s extreme compassion, silent yet present beside those who suffer. The new screenplay takes up and expands this theme. First of all, as mentioned, it is inspired by the same Endō, who in A Life of Jesus wrote that Jesus, living in an age of oppression and God’s silence, “brought the message of love and of a God who shares our suffering,” in contrast to the idea of a distant judging God. Endō emphasizes how Jesus “surrounded himself with lepers, prostitutes, with people who were ignored and ugly… loving even human failures,” and that it was precisely this love without practical utility that became his cross, because people sought miracles and power rather than mercy. Scorsese’s screenplay seems intent on showing that this message of suffering love is still alive today. Where is Jesus in contemporary suffering? In the small and great miseries of modern life—such as poverty, urban loneliness, injustice—Jesus continues to be present. For example, the scene of the beggar on the train highlights how an act of compassion (even just a gaze that recognizes the other) is a way of “carrying the cross” together with those who suffer. The young woman, by feeling empathy for the dirty and intrusive man, in a sense overcomes God’s silence with a gesture of love. This echoes the logic of Silence: in that film, the anguished question was why God remained mute in the face of the faithful’s martyrdom. The answer came in the form of a paradox: God spoke precisely in the silence of the most painful act of love, namely by allowing Rodrigues to betray Him for the good of others. In the same way, in the new screenplay “life never stops” and the world continues indifferently—as that young altar boy observed—but sparks of authentic faith occur in gestures of love that break through this indifference. In this sense, the new cinematic project is a continuation of Silence: it shifts the focus from seventeenth-century Japan to our present, but the underlying question is the same—how to believe and embody Christ’s love amid suffering and the apparent absence of God. It is no coincidence that the screenplay itself includes an explicit reference to Silence: during the montage of film clips in the text, Scorsese cites the scene of Kichijirō—the Japanese peasant who repeatedly betrays the faith—“who returns after yet another betrayal,” placing it alongside that of the veteran in The Irishman who asks for a door left slightly ajar, and alongside other images of characters “on the threshold of redemption, full of fear and trembling.” We thus see that the film places Silence in direct dialogue with the new discourse on Jesus: Kichijirō embodies human weakness and at the same time the hunger for limitless forgiveness, a central theme both in Silence and in Endō’s image of Jesus (a Christ who never tires of forgiving the “weaklings,” as Endō calls the fearful disciples). Scorsese himself has confided that making Silence was a transformative experience for him, “an attempt to understand the mystery of God’s love,” and that it changed the lives of both himself and his collaborators. The new screenplay arises precisely as a response to a spiritual appeal by Pope Francis to artists to “show Jesus with new languages,” an appeal launched in the preface the Pontiff wrote for a book of mine entitled A Divine Plot. Jesus in Countershot. Therefore, this screenplay probably represents the fruit of the transformation that began with Silence. If Silence ended on a note of painful ambiguity yet full of grace (the crucifix hidden in Rodrigues’s hands in the funeral pyre), the screenplay picks up the thread and asks: now, today, how can we bear witness to Christ in human suffering? The ideal continuation consists in “removing the negative aspects” that have made the Christian message inaccessible to many and returning to the essence of lived faith: love that draws near to the suffering person, even at the risk of misunderstanding and rejection. In conclusion, the new screenplay carries forward the reflection of Silence by shifting the focus from the tragedy of historical martyrdom to the daily tragedy of indifference. In both cases, authentic faith is revealed in the gesture of love that entails sacrifice: trampling an icon to relieve another’s pain in Silence; truly meeting the gaze of an outcast in the new film. It is the same Christ at work, “suffering with us,” yesterday in Japan and today in our metropolises—and Scorsese, continuing his artistic pilgrimage, seeks to show Him to us once again, in a different way but one that is spiritually consistent with Silence.

A few months ago, Martin Scorsese revealed that A Life of Jesus, based on the book by Shūsaku Endō, the same author whose work inspired Silence, will be a low-budget film and probably shot in black and white. Can this be interpreted as a desire on the part of the great New York director to return to his roots as an independent filmmaker?

Scorsese has stated that this new film about Jesus will be shot in black and white and with a very modest budget, marking a clear shift from his recent blockbusters costing over $100 million. Speaking at the Taormina Film Festival 2025, he revealed: “I’m still working on it… it will almost certainly be in black and white,” adding that the project will be “largely set in the present and independently financed,” making it “one of the least expensive films he has made in a very long time.” This choice carries a dual meaning, both artistic and autobiographical. On the one hand, the black and white aesthetic and the low budget hark back to Scorsese’s origins as an independent auteur. His early films in the late 1960s and early ’70s (Who’s That Knocking at My Door?, Mean Streets) were made with limited resources but with enormous creative fervor, becoming a manifesto of how “cinema could above all be a form of art,” beyond big means. Returning today to a small, intimate film—perhaps shot on 16mm or in any case far removed from sophisticated digital productions—represents for Scorsese a return to that poetics of expressive urgency typical of independent cinema. Works like Mean Streets demonstrated a “tremendous creative audacity” achieved with scant means; similarly, Scorsese seems to want to rediscover that expressive freedom, unbound from the commercial logic of the major studios. A reduced budget, in fact, allows him to follow his spiritual vision without compromise, in a project he describes as long in the making (“it requires years of study and research,” he has said) and decidedly non-commercial (an 80-minute, experimental religious film is certainly not a blockbuster). It is a countercultural choice that can be interpreted as an act of fidelity to his artistic vocation: having passed eighty, Scorsese prefers to invest time and energy in a personal film about faith, even a small one, rather than chase another major mainstream success. On the other hand, the decision to shoot in black and white also carries a poetic meaning internal to the work. Black and white immediately evokes an aura of essentiality and timelessness, perhaps deemed more suitable for a spiritual narrative. Scorsese has cited Pasolini’s The Gospel According to Matthew as a reference—a black-and-white film that impressed him so deeply that at the time it led him to set aside his own idea of making a film about Jesus, because he felt Pasolini had already achieved an unsurpassable cinematic truth.

Now, choosing black and white can be seen as a tribute to that Pasolinian lesson of rigor and authenticity. Pasolini filmed Christ in a stark, almost documentary-like way, emphasizing the contrast between light and shadow in the Gospel message. Scorsese, in his small film, seems to want to do something similar: to “make the film more accessible” by stripping it of any gloss or chromatic distraction, so as to focus attention on the face, the word, the message. Black and white eliminates the superfluous and “abstracts” the story from a specific present, giving it that sense of timelessness the director desires. He has in fact said that he does not want to rigidly anchor the story to a particular era, but to aim for something “timeless.” Moreover, black and white could encourage bolder and more personal expressive solutions—think of light contrasts that can take on symbolic value. In practice, Scorsese embraces an “indie” aesthetic not only for budgetary reasons, but because it is consistent with the “new language” with which he wants to speak about faith: a visual language closer to the stripped-down truth of experience, far from the reassuring or spectacular colors of conventional Hollywood cinema. Finally, the low budget implies a production outside the major systems, which is also significant on an ideological and poetic level: Scorsese returns as a complete auteur, much as in the New Hollywood of the 1970s, when directors fought for final cut and creative independence. After many films financed by major studios or platforms with high economic return requirements, he likely feels the need for a human-scale, almost artisanal project, where he can freely experiment even with narrative form (he has spoken of “something that is not quite traditional fiction, nor a documentary, but a hybrid”). This freedom is typical of independent, auteur-driven cinema. It is not surprising that, to support the project financially, Scorsese has sought independent backers: this allows him not to be accountable to market logic (short running time, religious themes with little commercial appeal—choices that a studio would hardly approve). Therefore, yes: the new film about Jesus represents for Scorsese a return to indie poetics, both in its minimalist visual style and in its production spirit. It is a return to origins motivated by the urgency to tell something deeply felt (“I’m responding to the Pope’s call in my own way, imagining a film about Jesus”), placing art and faith at the center and relegating business to the background. In an era in which Scorsese himself often criticizes a Hollywood industry dominated by soulless comic-book movies and franchises, this black-and-white film about Jesus can indeed be read as a manifesto—yet another—of his love for a personal, spiritual, and free cinema, born more from the need for expression than from market logic. In this sense, the operation ideally dialogues with the young Scorsese of the 1960s: closing the circle, at the end of his career he returns to that lightweight 16mm camera, to the dreamed-of black and white, to speak about the one subject that has always fascinated and challenged him: “Who is Jesus for us, today?” And he chooses to do so with the purest tools of cinema, almost to remind us that sometimes all it takes is a light, a shadow, and a face—like the icon of the Pantocrator illuminated for a minute at Sinai—to touch the mystery. No grand effects or huge budgets are needed, only a sincere gaze and the courage to use it. Ultimately, the low budget and black and white are more than technical choices: they are a poetic declaration of intent by Martin Scorsese, confirming that his artistic journey has returned to its roots, where making cinema is akin to making an act of faith.