Who is Filippo Ulivieri?

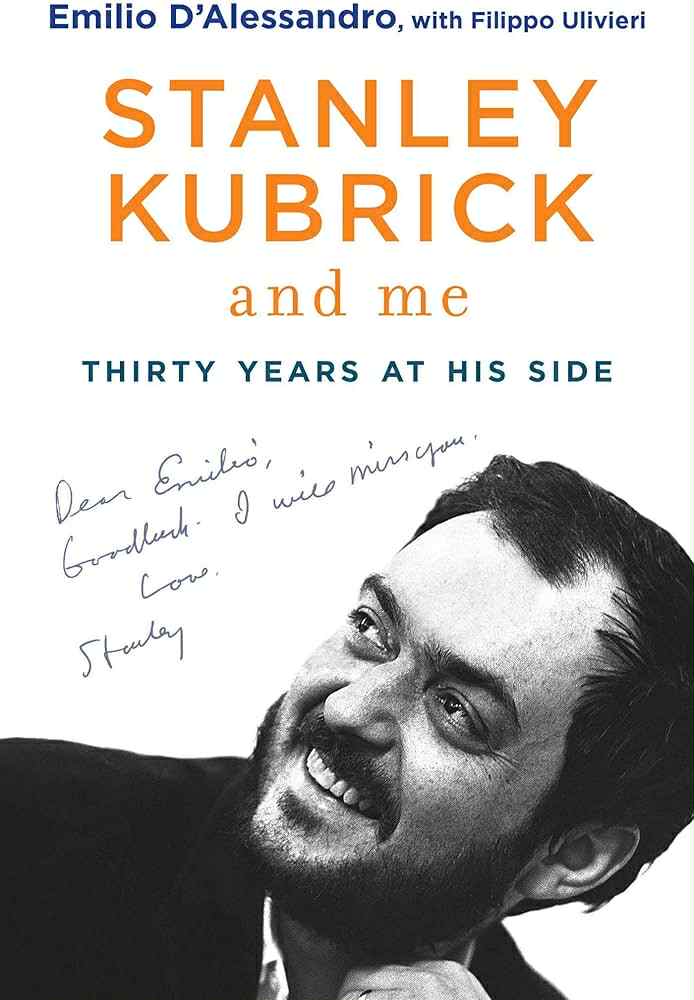

I’m a narrative non-fiction writer who has so far focused mostly on Stanley Kubrick. After the publication of my first book, Stanley Kubrick and Me: Thirty Years at His Side, in its English translation, I was described by The New York Times as “Italy’s leading Kubrick expert.” I have been studying Kubrick’s life and films for about twenty years and have now written four books and numerous essays on different aspects of his work. I also adapted Stanley Kubrick and Me into the documentary S is for Stanley, which won the David di Donatello Award for Best Documentary Feature.

Tell us about the Kubrick Archive in London, what were the most surprising discoveries you made there?

My work on Kubrick is always based on new, original research. I interview people who worked with and knew Kubrick well, and I visit archives — the largest and most important of which is, of course, the Stanley Kubrick Archive, held at the London College of Communication, University of the Arts London. It contains material donated by Kubrick’s widow Christiane after his death, ranging from film scripts and correspondence with collaborators to research he conducted, behind-the-scenes photographs, and artefacts such as costumes and props. It is a treasure trove of daunting scale and a unique source for understanding, truly and for the first time, how Kubrick worked.

It is difficult to single out one particularly revealing item. I can tell you what surprised me most on my last visit, when I was studying the long and convoluted creative process that culminated in the production of Eyes Wide Shut. I knew that Kubrick wanted to adapt Schnitzler’s Traumnovelle as early as the late 1960s, but I had no idea how extensively he revisited the project in the early 1980s. He corresponded with Schnitzler’s nephew and had Schnitzler’s own adapted screenplay — written in the 1920s for a proposed film by G. W. Pabst — translated into English. Comparing that script to Eyes Wide Shut, it becomes clear that Kubrick incorporated several ideas from Schnitzler’s version. Kubrick even drafted a preliminary production plan to shoot the film in London standing in for New York, with Steve Martin and Meryl Streep as the leads. I can’t wait to understand it all better and write about it in my next book.

A.I. Artificial Intelligence, directed by Steven Spielberg in 2001, was originally a Stanley Kubrick project, an work that stages one of the central debates of our time, namely to what extent AI can be a resource and how to prevent its misuse, potentially even harmful uses. Did you find information in the Kubrick Archive about the original project that differs from what ultimately became the film?

A.I. was always conceived as a fable, and when Kubrick wrote it there was little available information about artificial intelligence as we understand it today. The story revolved around intelligent robots capable of performing specific tasks, reflecting the predominant view of AI at the time. From the drafts and notes Kubrick left, I would say his main concerns involved the evolution of the human species through technology — quite literally as hybrids between organic and mechanical life. The latest drafts are more abstract, as is Spielberg’s completed film.

The film we know is obviously different from what it might have been had Kubrick directed it, but it remains faithful in terms of story and character — at least to Kubrick’s latest drafts. The issue is that Kubrick kept rewriting the project, alone and with another writer, so we simply cannot know where he would ultimately have taken it. It is not just a matter of directing, but of development. Spielberg wrote the screenplay and directed the film based on the second-to-last treatment and the preparatory work Kubrick had done. But Kubrick was still revising the story when he abandoned it in 1995, so the point I tried to make in a chapter of my book Cracking the Kube where I chronicled the development of the film is that we will never know what A.I. by Stanley Kubrick would have been.

I consider 2001: A Space Odyssey to be the Sistine Chapel of the 20th century: just as Michelangelo’s work in the 1400s represented the pinnacle of artistic expression, the same is true of Kubrick’s film. Can you reveal something surprising about this infinite masterpiece that we haven’t already heard?

The surprising fact is that the film as we know it emerged almost at the last minute. 2001: A Space Odyssey is the perfect example of Kubrick’s working method — he kept generating new ideas until the very end, often reshaping the project entirely. As I explain in my book 2001 between Kubrick and Clarke, the film began as a fictional documentary about the early stages of human space exploration; over four years, it gradually evolved into a mythological statement about humanity’s place in the universe.

The most radical change — when Kubrick moved away from Arthur C. Clarke’s more literal and scientific approach — occurred only at the end of their collaboration. In the last five or six months, Kubrick made the decisions that transformed the film’s tone and feel: he eliminated the voice-over narration, which explained much of the action, cut several dialogue scenes, and used music to guide emotional responses. We often imagine a genius filmmaker who executes a perfectly designed plan, but with Kubrick nothing could be further from the truth. He knew what he did not want, and worked tirelessly to discover new and more compelling ways to tell the story he had chosen. Nothing in a Stanley Kubrick film was fixed from the beginning.

WILD FILMMAKER is a global movement created to support independent authors; we aim to be what James B. Harris was for Stanley Kubrick. Without James B. Harris, we certainly wouldn’t be here today talking about the greatest American director in the history of cinema. Do you think our work is useful, and that people who discover and help launch artists with an original vision are missing—or are rare—in today’s contemporary film industry?

My view of the current film industry is too limited for me to speak with any authority. It is true that without his partnership with James B. Harris it is possible — if not likely — that Kubrick would have remained on the margins of American filmmaking. But Harris did not “discover” Kubrick, nor did he nurture him as a patron or mentor.

They were equal partners who wanted to make good films, and they were both satisfied with their roles: Harris as a producer who could also write, and Kubrick as a writer-director who also understood the production side extremely well. Their split happened, in fact, because both wanted as much creative control as possible. Harris and Kubrick were true soul mates in their approach to cinema and to art in general, and Harris’s influence on Kubrick is often underestimated.

Given your intense study devoted to the filmography and biography of Stanley Kubrick, I’d like to ask you a question that touches on your unconscious: have you ever dreamed of him?

I must have, given how much of my daily work revolves around him, but I don’t recall any specific dream. Perhaps I think about his films enough while awake that my subconscious needs a break!