– How and when did you meet Andy Warhol?

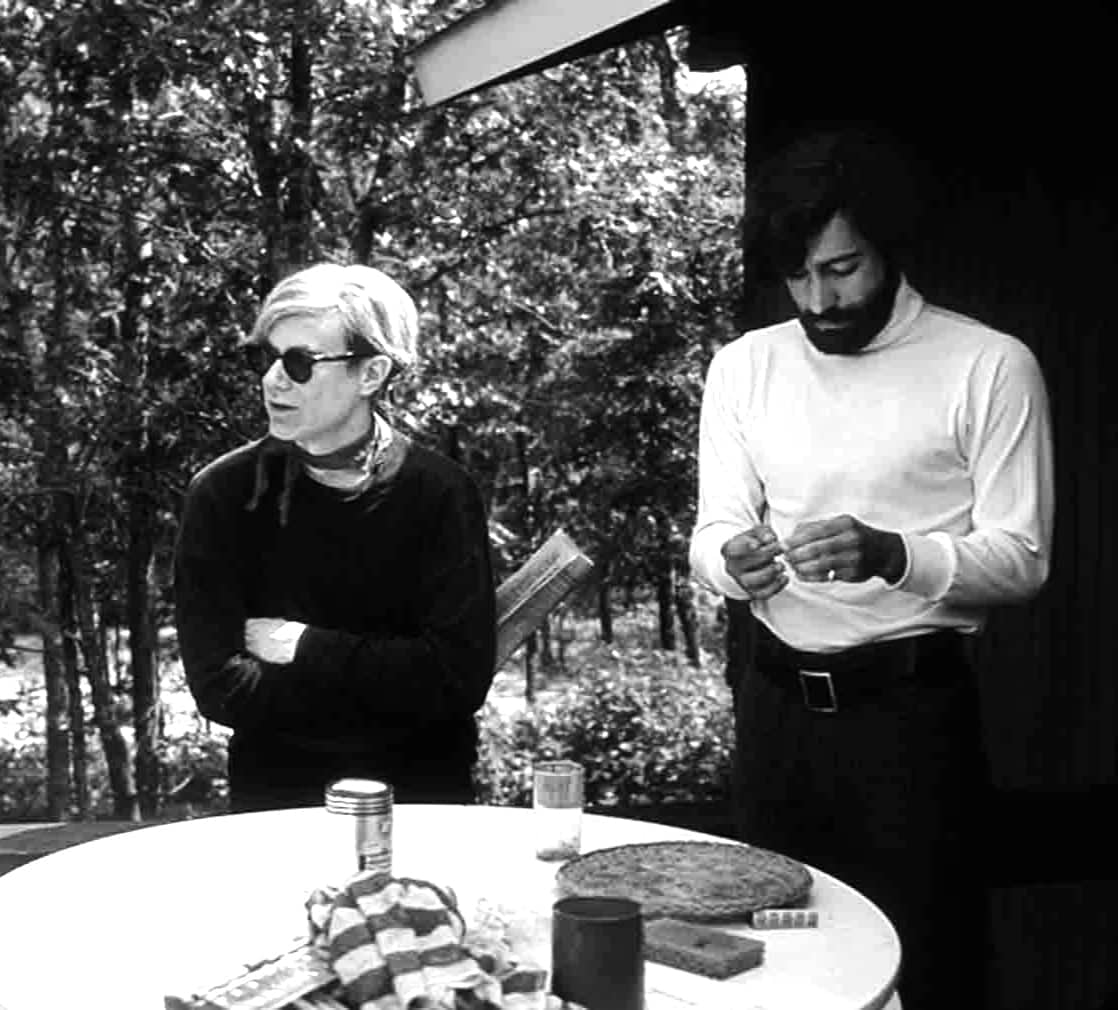

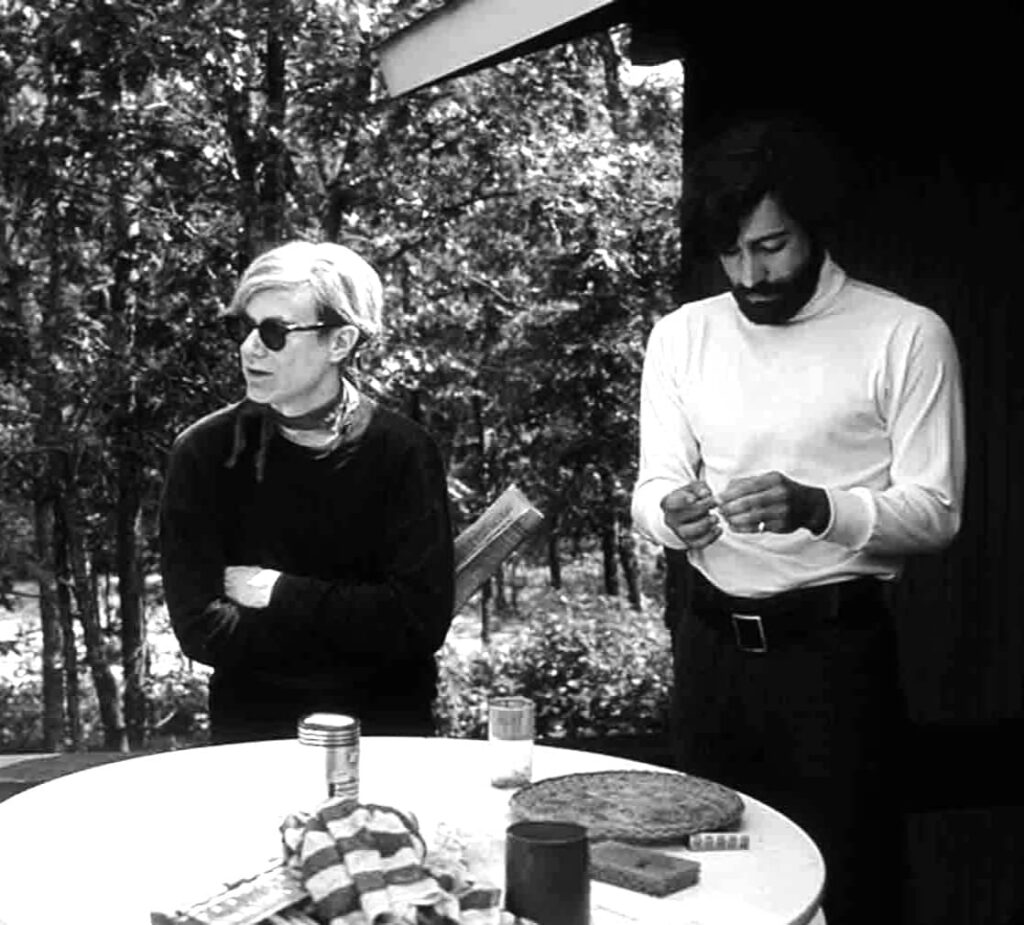

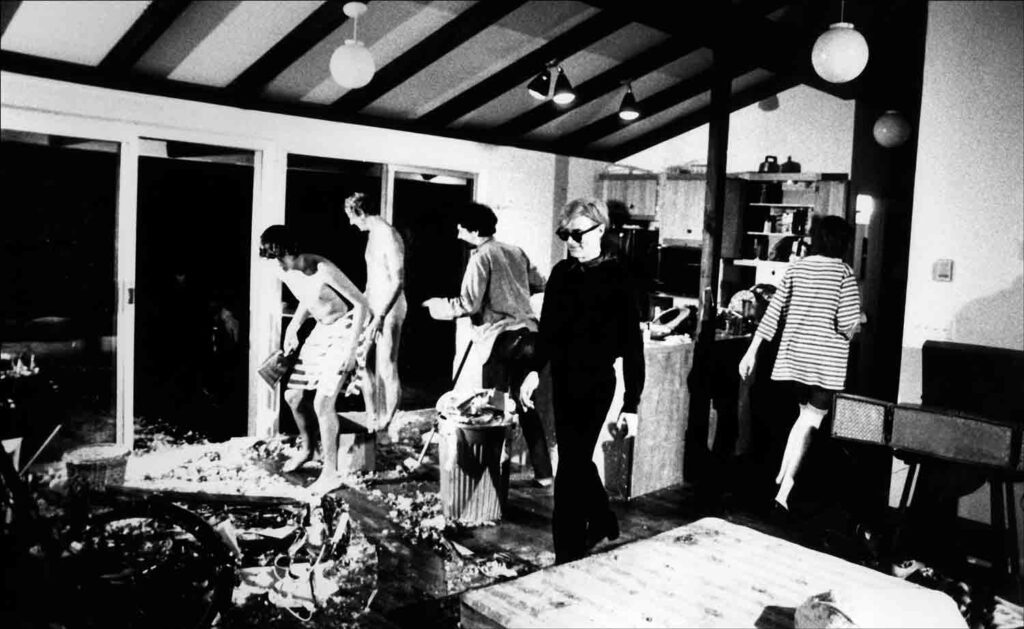

I met Andy in New York in 1963. This year I was invited by the Martha Graham Dance Academy to take an intensive course in contemporary dance. Once in New York, I met Harold Stevenson, a well-known American painter at the time, at an opening at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. He invited me to a cocktail dinner given by Adelaide de Menil, a photographer and the daughter of John de Menil, a famous art collector during that time in New York. The youngest of her daughters founded the Dia Art Foundation, a renowned organization whose mission was to promote artists. At that dinner was Andy Warhol, and Stevenson introduced him to me, we greeted each other, and that was it. When the dance course at the Graham Academy concluded, I returned to Venezuela for the next two years, and it was in 1965 that I finally settled in New York. Manhattan seemed to be a melting-pot city where crucial things in relation to art were about to happen. When I arrived, I stayed at the YMCA on 23rd street, just across the Chelsea hotel. One day, I invited a dancer friend of mine to have dinner at a Spanish restaurant called “El Quijote” at the Chelsea Hotel. When we sat at a table, Warhol and some of the Factory members were next to us. I was intrigued when I saw Gerard Malanga approaching me to tell me that Warhol liked my style and presence. Back then, I used to dress in black with a cape. Malanga and I barely were able to communicate partially in English and partially in Italian; Warhol wanted to know if I would like to be part of his next film. I responded that certainly yes, but it wasn’t until another day I saw my friend Waldo Díaz-Balart that I heard from them again. Waldo told me that Warhol was going to shoot a movie at his house in the East Hamptons, he knew that we were friends and wanted to know if I was still interested in playing a role in the movie, so once again I said yes. Waldo and I became friends one day I was walking through the East Village when I first went to New York in ’63 . And that is how my group “Foundation for the Totality” and I participated in the filming of “Four Stars,” a 24-hour movie in which I performed a happening called “THE PAELLA- BICYCLE-TOTAL- CRUCIFIXION”.

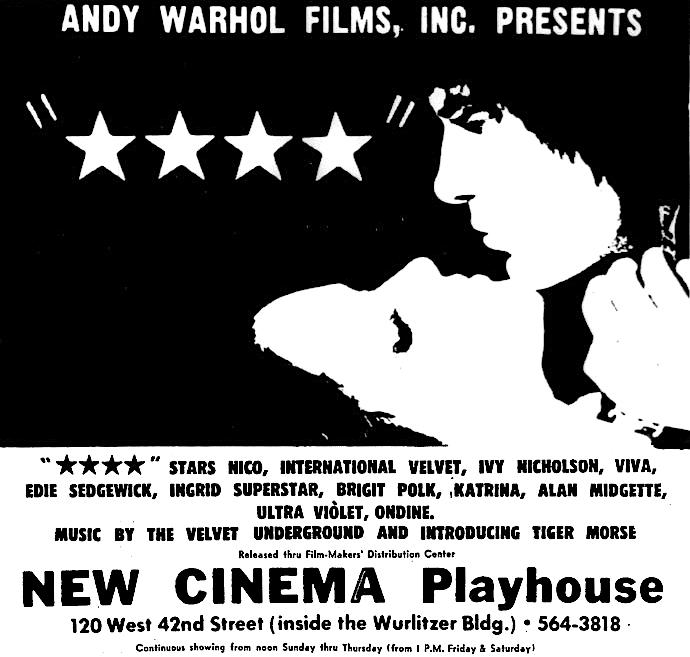

-You’ve made several experimental movies with Andy Warhol… Tell us about it…

After “Four Starts,” I made some other films with the Factory, among them “The Nude Restaurant” and “The Loves of Ondine.” Besides the movies, I also collaborated with the Factory on many exhibition projects like for example, the idea of Mao Zedong was one of mine that I shared with Andy, and like that, many others that he thought were very good.

-What are your memories of the Factory?

I have unforgettable memories of the Factory and its members. It would be worth doing a full interview since only about it since there is a lot to tell: Gerard Malanga, Joe Dallesandro, Edie Sedgwick, Viva, Ultra Violet, the photographer Billy Name, and Paul Morrisey, who was the one who actually shot the movies, and so many others. My collaborations spanned various disciplines, in particular, I participated in the initial conversations about the “Interview” magazine project and in the first issue that was made, which was a silver box filled with various objects. Being part of the Factory was an extraordinary experience that marked my life as a before and after.

-How was Andy Warhol’s New York City?

Andy was an outstanding character and unquestionably a great genius. Andy perfectly understood and knew how to project the spirit of that magnificent city.

I have always said that Andy Warhol is a great documentarian, one of the most brilliant I have ever met. He knew how to capture the energy, the characters, the odors, the creativity, and the underground poetry that emanated from the asphalt of the streets of New York. Undoubtedly, the rarefied, polluted air that we breathed in the midst of that immense mass of concrete of its skyscrapers transmitted a powerful energy that urged us all not to stop, to keep going and cross the tightropes without a protective mesh. The sensation of the risk of the unknown, of the encounters, was a source of immense inspiration we transformed into urban poetry. No doubt that Warhol understood all this and wrote his memorable story.

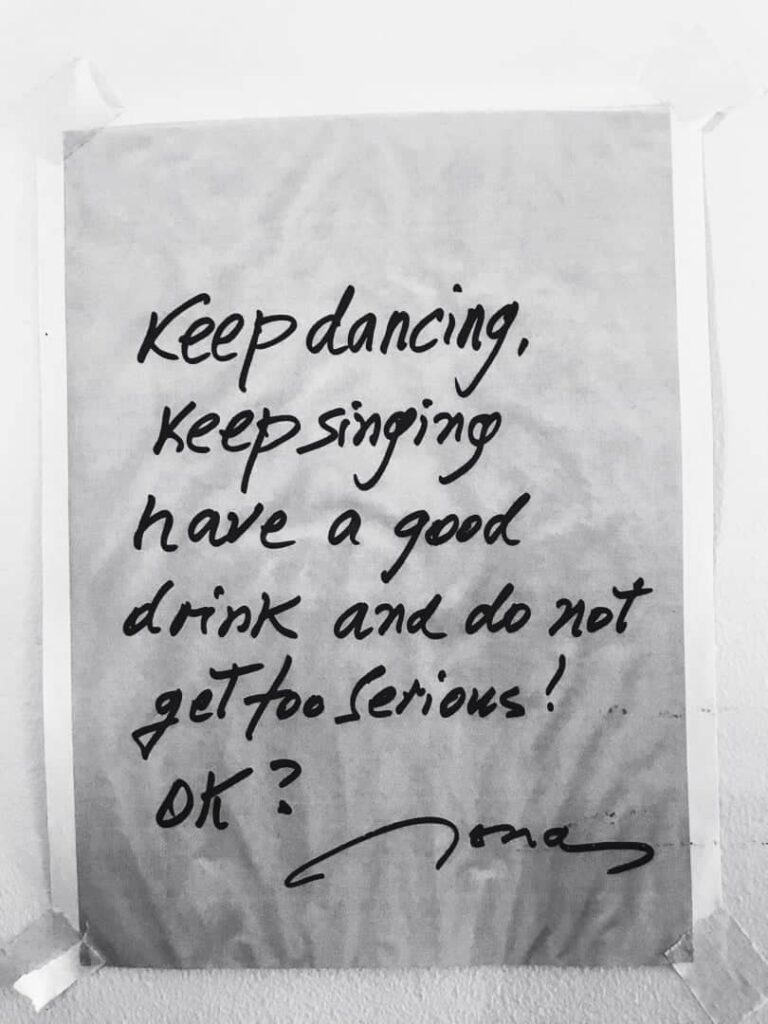

He was an extraordinary and brilliant artist with whom I have great memories, very close memories, and great solidarity. I hope he is well, and that he is having a great time, and I would not be surprised if he is also recording and photographing this interview that he will surely publish; so get ahead of him and post it before he does.

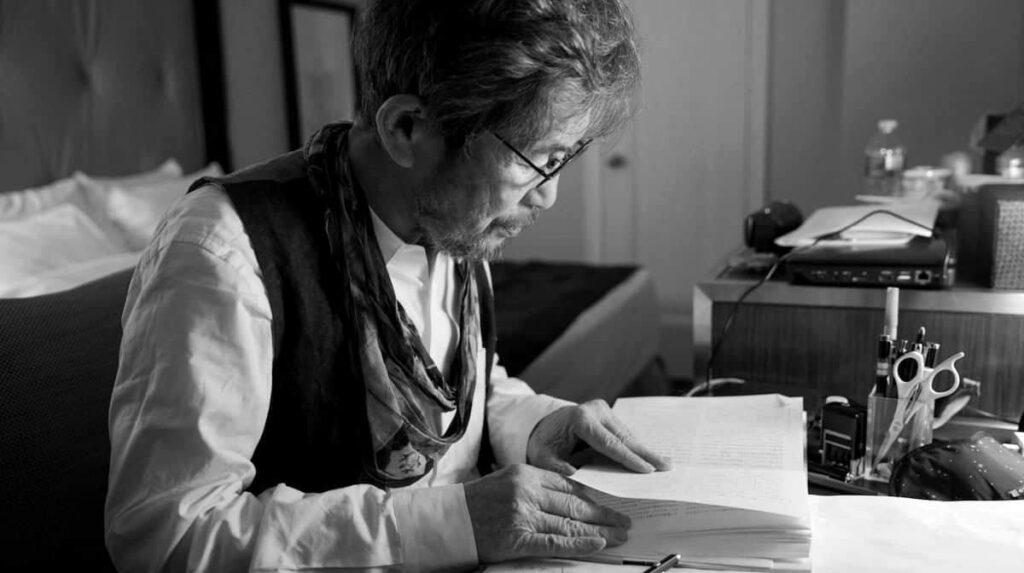

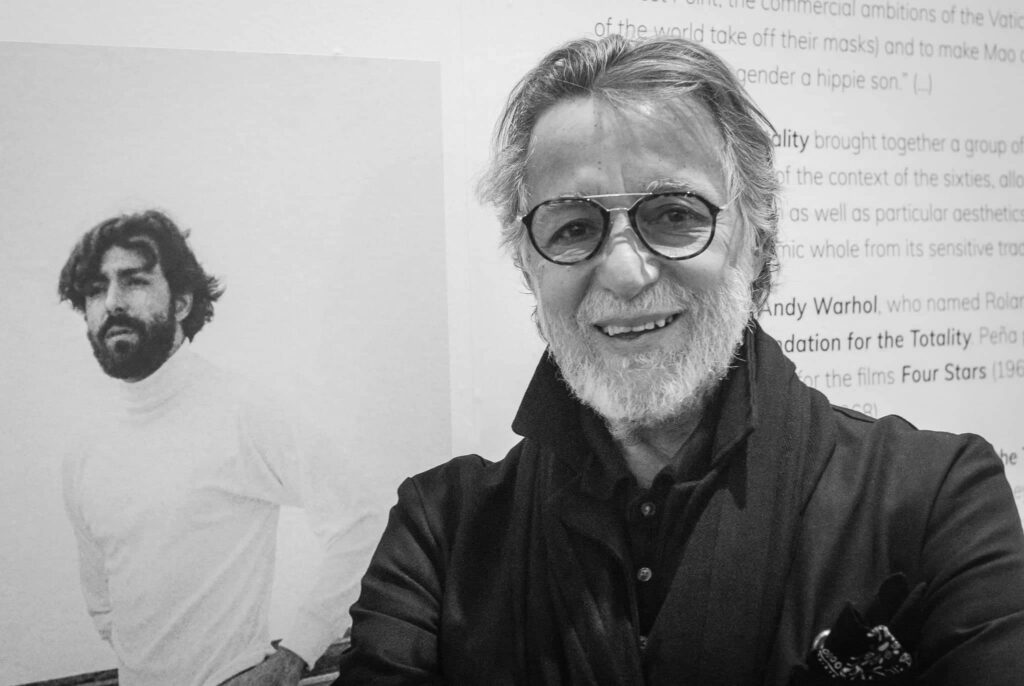

-Who is Rolando Today?

Rolando Peña today is an avant-garde artist as he has always been, a tireless researcher with extreme curiosity accompanied by infinite energy. Rolando Peña has survived all the prejudices, denials, and infamy of the ignorant. The figure of the “Black Prince” is gone. It served as a shield for me in the sixties, but now it has turned against me. Several times I have tried to make him disappear, to bury him, but he is extremely stubborn, and it reborn again. However, I am Rolando Peña, his creator, and I am much more significant and thought-provoking than him. I currently live in Miami, but I work for the world. I live with a wonderful woman, Karla, my angel, whom I love enormously; we are blissful.

I can tell you that I still have many years to live to continue creating art accompanied by science and technology. So get ready, all the good is just starting.