Those of us who love, live and breathe cinema all have our own journey, each one as unique and diverse as we ourselves are. Whatever makes us fall in love with the art of the moving image, be it the craft of Kubrick, the weirdness of Ken Russell, the poetry of Tarkovsky, the beauty of Agnes Varda, the physicality of William Friedkin, the lavish storytelling of Bela Tarr, the sentimentality of Steven Spielberg, the epic vision of Jodorowsky, the passionate humanity of John Cassavetes, the grittiness of Martin Scorsese, the wild dreams of François Truffaut, or the sheer guts of Jean-Luc Godard, there is one name above all others that unites us, and all of these, and that name is Federico Fellini.

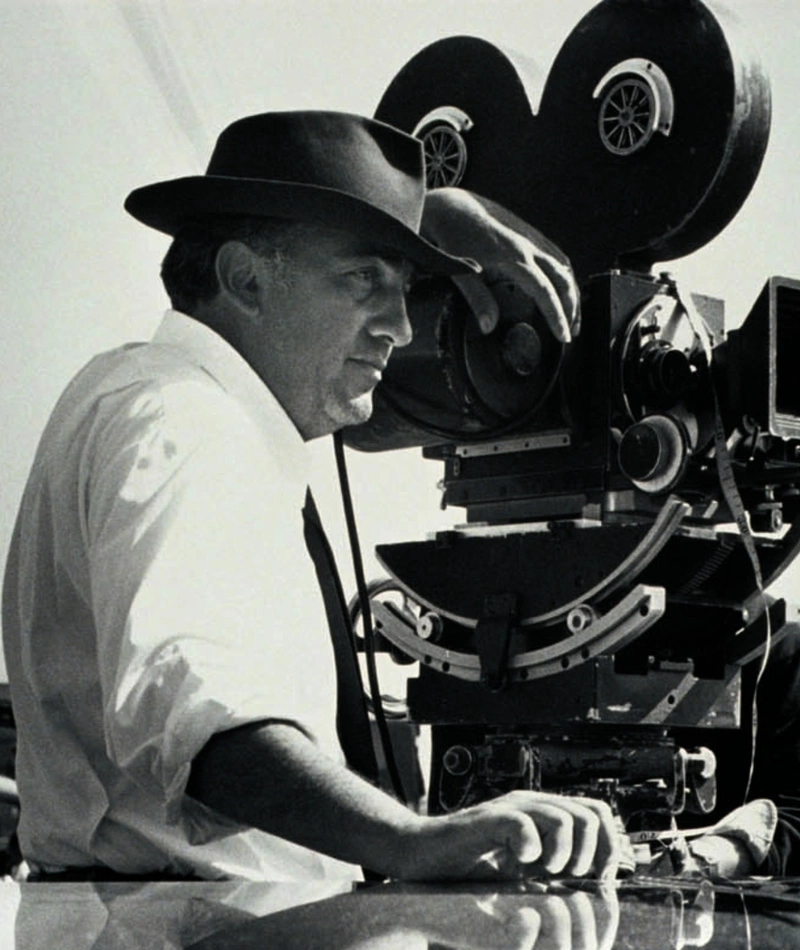

From his humble beginnings as the son of an apprentice baker, his break as co-writer of Roberto Rossellini’s post-war classic Rome: Open City, through his time at the forefront of Italian Neo-Realism, to his later work that was so unlike anything before it that the word “Fellini-esque” had to be invented to encompass it’s unrelenting originality, Fellini’s films stand as works for ages, like the paintings of Vermeer or the plays of Shakespeare. I myself regard Fellini as the Shakespeare of Cinema, and his is the work I return to time and time again, whether in celebration or times of self-doubt. There is always something in his films to move and inspire me anew, and there is no more valuable an asset for any artist than inspiration.

We do not attempt to copy Fellini, we know we cannot. If we did it would be substandard to anything he created, and artifical, and we know that. Instead, Fellini inspires us to dig deeper and push farther to find our own cinematic voices. His work, like the stream-of-consciousness writing of Virginia Woolf, is a constant source of power and enlightenment to any audience willing to receive it’s gift. But still he is much more than just the filmmaker’s filmmaker. Fellini represents the peak of human artistic endeavour. His work crosses all barriers; language, gender, realism, surrealism. The ultimate agnostic, open to everything, closed to nothing. Fellini could go anywhere and be anything. His characters were flawed and as human as any of us, yet they could have spiritual awakenings and fly off the face of the Earth without losing a grain of their humanity. Fellini was constantly showing us not only who we are, but who we could be, all of the great things human beings could do if they only set aside their smallness and their insecurities. Above all Fellini showed us how to love ourselves so that we could come to understand how we can love others. He demonstrated the sheer poetry of being alive, the beauty of just existing.

I first encountered the work of Fellini at the age of 18 when Derek Jarman loaned me a VHS tape of La Dolce Vita. I had read about the film in Richard Witts’ biography of German singer Nico, who had appeared in it. I’d seen the films of Ken Russell, and Derek too, also those of Visconti, Nic Roeg, Donald Cammell, a couple of things by Truffaut. But I think I still considered the Hollywood legends, such as Michael Curtiz, Billy Wilder and Frank Capra, as the great masters of cinema. All of that changed when I saw La Dolce Vita. I had never seen anything executed as perfectly as the Trevi Fountain scene, and maybe I still haven’t, and the movie completely changed my ideas about cinema. Fellini showed me that there were no rules, no limits to what cinema could be. I sought out his other films, discovering in the process that I Vitelloni was Stanley Kubrick’s all-time favourite movie, Satyricon was Ken Russell’s, and countless names cited Fellini’s 8½ as the greatest film ever made. It all made such perfect and weirdly wonderful sense to me.

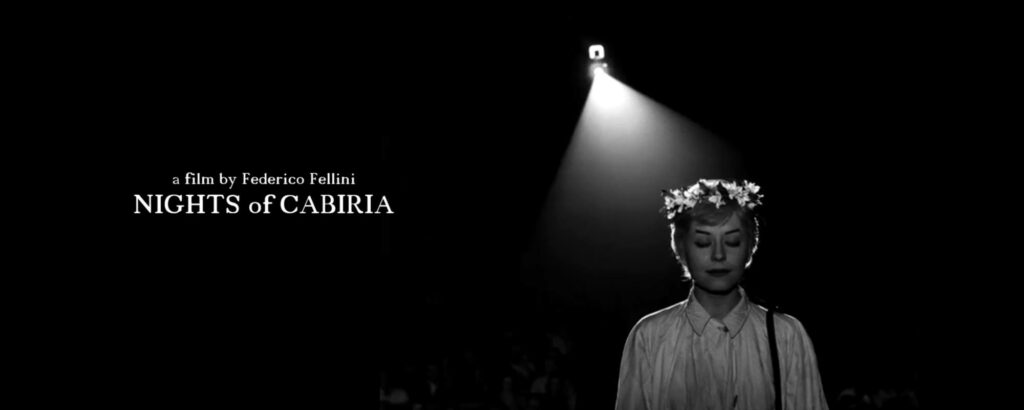

When Fellini died it was world news, and I understood the true impact of his work for the first time. As the tributes rolled off the presses, it turned out that everyone that I revered, from David Lynch to Sally Potter, revered Fellini, and that there really wasn’t anyone above him. And then I saw Nights of Cabiria for the first time. It broke my heart and it blew my mind more than any other film ever has, the sheer depth and beauty of it completely redefined what I would ever after hunger for in cinema. And when it seemed to me that no one was even trying to dig that deep any more, that’s when I took up filmmaking.

It turned out that I was wrong, there were and are plenty of gifted filmmakers who absolutely aspire to the depth and feeling of Fellini, and some may even have the talent to do it, if they could only get the funding to try. Quickly I understood that the need to experiment and take risks in order to find that voice and vision, that truth in us that gives us any chance of following in the Maestro’s footsteps, also out of necessity required the willingness to fail. And therein is the trouble, money only measures success in financial terms, and that quite useless when you are reaching for the proverbial stars. As filmmakers and artists we cannot afford the cowardice of commerce, and yet everything costs money. There seemed to be two possible ways to address this; either kow-tow to the benders of commerce or simply make films that cost less to make. The latter approach seemed to work for Derek Jarman and Kenneth Anger and Werner Herzog. And thus I tried, in 8mm and 16mm and MiniDV, and I made a film, Albion Rising, starring Dudley Sutton reciting the words of William Blake. I had met Dudley when he was working on Edward II with Derek and Derek’s muse Tilda Swinton, with whom Dudley also worked on Sally Potter’s Orlando (both films owing much to Fellini’s later work.) Dudley had worked with everyone, the best of the best, but top of the list was Fellini, as he had appeared in Casanova. So Dudley’s first day working with me consisted of my bombarding him with the burning question, what would Fellini do?

When one finds one’s own true inner voice, it is inevitably linked to our inner child. Our ability to recognize the truth has grown from our childhood need for trust. As such there is a direct line between truth and innocence. Once we understand this about human nature, and once we understand that there is more to living then simply reacting to what the world throws at us, writing a screenplay is simply a matter of working out how to use the software. It cannot be learned from any book or classroom, but it is there on the screen before our very eyes in every film Fellini ever made. Fellini understands that the worst thing we can ever be in this life is an adult, because with adulthood come responsibilities which we never asked for and never really wanted. Our deepest desire is to break free, even if just metaphorically. We do not have a duty to obey the rules, only to break them. But we don’t seek to break them as a conscious rebellion, but merely as a byproduct of going our own way. Our inner child knows what we really want even when we don’t. We must become humble in order to hear it. Fellini was the humblest of men, an example to us all.

As independent filmmakers, the revolution was on our side with the advent of digital cameras, particularly the DSLR that could, in theory, shoot video almost as well as a 35mm Single Lens Reflex could shoot stills. With the technology now in our hands, our emphasis could become ideas. With minimal funding it became possible to surround ourselves with talented people. The trick now, then, would be to have something actually worth filming. And so the journey towards the within could finally begin, as we write our hearts out, hold nothing back, and whenever we get stuck, ask ourselves the big question, again; what would Fellini do?

To this day my greatest ambition in cinema is to create work that has at least at it’s heart something of the magic of Nights of Cabiria. I am driven by it, compelled by it, it is the Holy Grail of filmmaking for me. One image as beautiful as the backlit shot of Cabiria on stage with the flowers in her hair, one ending as heartbreakingly beautiful as the ending of that film. Then I would not have lived in vain. I turn once again to the words of Virginia Woolf, my other greatest muse: Survive, create beauty, tell the truth.