By Michele Diomà

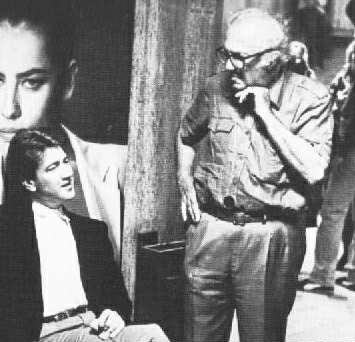

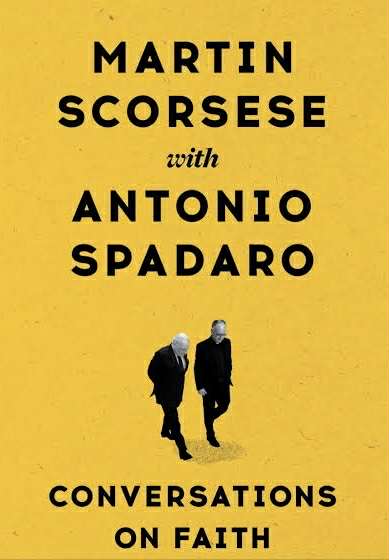

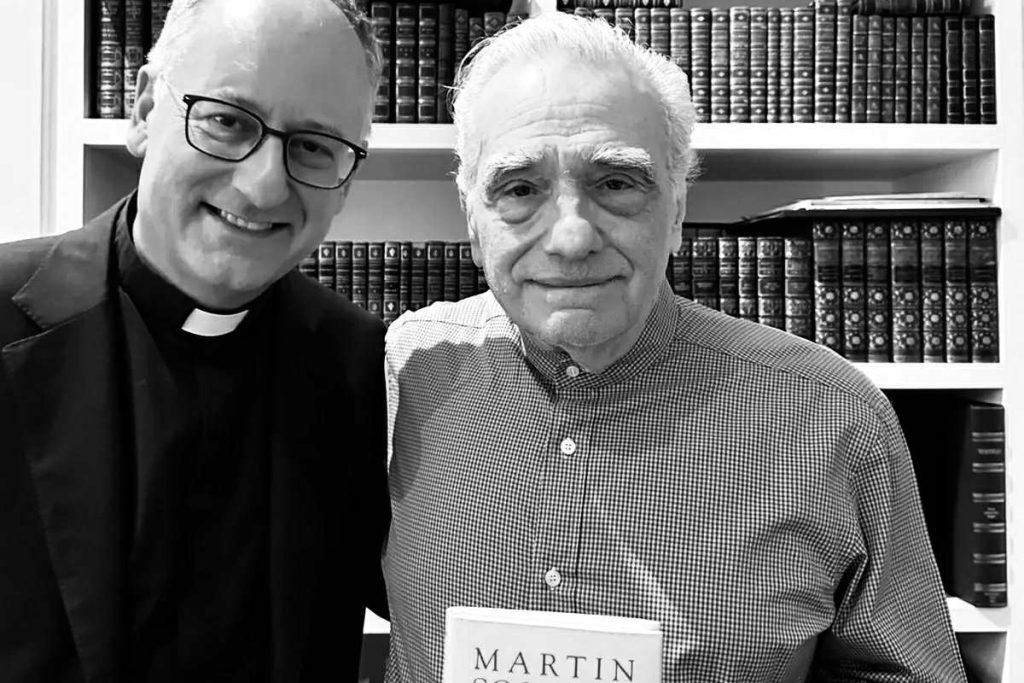

Today a great gift was given to the entire WILD FILMMAKER Community, since the early cinema of Martin Scorsese has been one of the main sources of inspiration for the birth of our International Movement. Films such as “Who’s That Knocking at My Door” and “Mean Streets”, made between the late 1960s and early 1970s with limited financial resources and tremendous creative courage, still stand today as proof that cinema can above all be a form of art. Spirituality and religion have always been central themes in Martin Scorsese’s filmography, and today we have the opportunity to discover exclusively how Conversation on Faith, the beautiful book written by the great director together with Father Antonio Spadaro, came to be.

-How did the project of writing the book “Conversation on Faith” with Martin Scorsese begin?

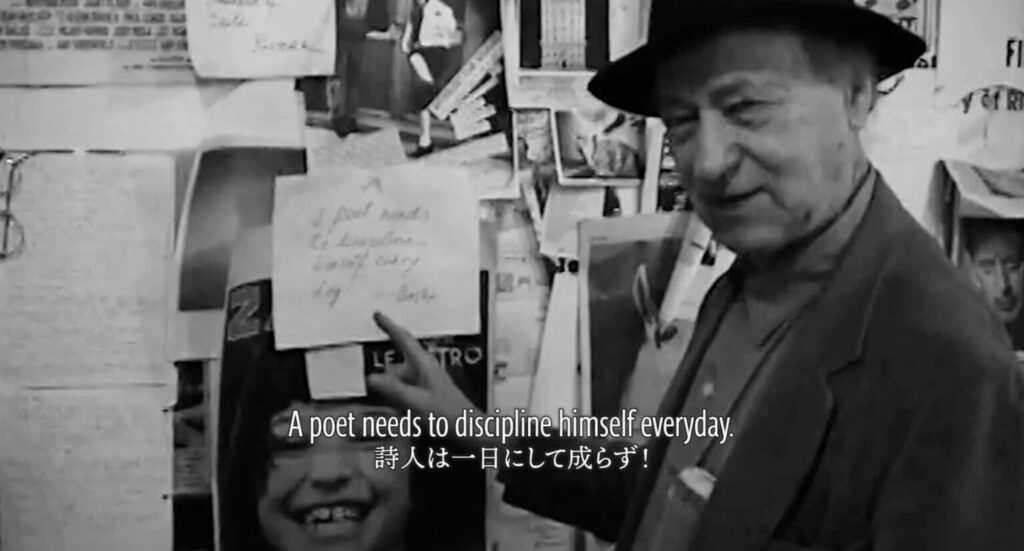

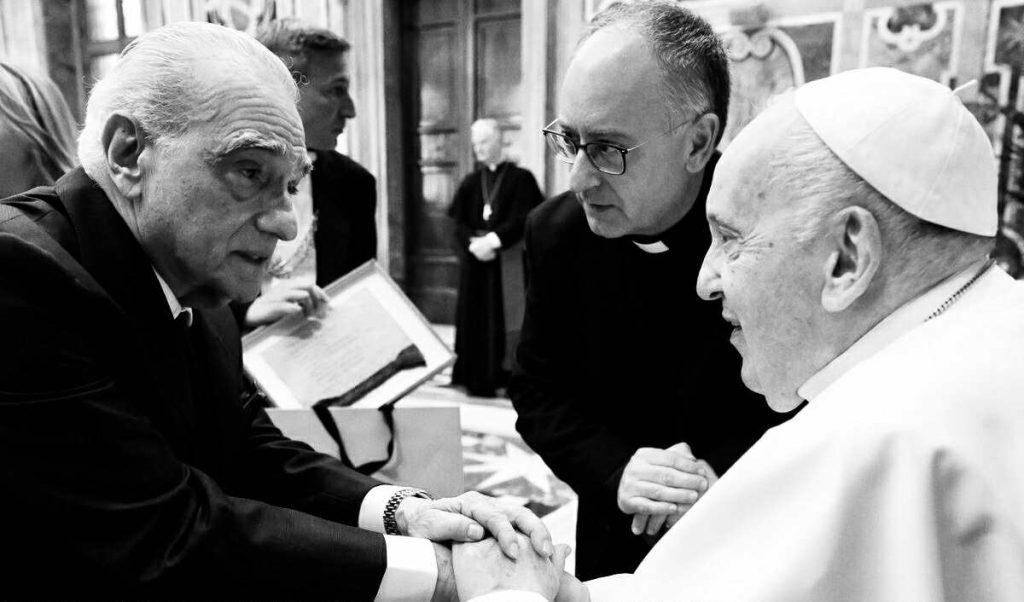

The dialogue began almost by chance, in March 2016, when I rang the doorbell of Scorsese’s home in New York for a simple interview about Silence. I was there for a journalistic assignment, and it could have been a one-off meeting. Instead, from that lunch a shared human and spiritual journey began, one that has lasted for years. We discovered we were “paisani”: his roots are in Polizzi Generosa, mine in Messina. This shared origin, combined with a passion for faith and for storytelling, melted the distance instantly. We didn’t talk only about cinema, but about life: his childhood as an altar boy in Little Italy, the tension between the dramatic beauty of the liturgy and the violence of the streets, the searing question of a boy who leaves Mass wondering why the world hasn’t changed after the Eucharist. From there the dialogue continued in stages: meetings in Rome, dinners at his home, his participation in the book Sharing the Wisdom of Time and in the Netflix series with Pope Francis, our correspondence during the pandemic, all the way to the Pope’s appeal to artists to “help us see Jesus in a new language,” which Martin took seriously by writing a first screenplay about Christ. The book “Conversations on Faith” is the fruit of this eight-year conversation: not a theoretical exercise, but the faithful record of a friendship in which faith, grace, and cinema have continually questioned one another.

-Cinema has often been a vehicle for spreading the Catholic faith; I’m thinking of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s “The Gospel According to Matthew”. What is your opinion of the film that will be discussed at today’s event in Rome with Martin Scorsese?

Pasolini recounts that Matthew’s text triggered in him a “terrible, almost physical energy,” an instinctive adhesion to the immediate moral beauty of the Gospel. This is crucial: his Christ is not tamed; he is a man who speaks against the wind, filmed in close-ups that cut through the gaze. He is an apocalyptic, piercing Jesus, close to the extreme anatomies of El Greco. For me, the peak of the film remains the scene of the Beatitudes: a young, hieratic face, eternal words spoken against a black, wind-swept sky. There is no sweetness, there is an almost unbearable tension, and it is precisely there that a beauty erupts which asks no permission. Pasolini, a secular Marxist, is not engaging in an ideological operation. He takes Matthew’s text as a ready-made screenplay, chooses to remain faithful to it word for word, and in a famous letter declares that he never wishes to wound the sensibilities of believers. His Christ is radical and uncompromising, but not opposed to Catholic tradition: he challenges it, forces it to take a stand. The December 5 meeting with Martin originates exactly here. Scorsese told me that when he was a student he dreamed of making a film about Jesus, but when he saw Pasolini’s Gospel he realized that what he had hoped to do had already been accomplished. For both of them, that film is a permanent provocation. The Roman event aims to show how a work born from the gaze of a restless secular artist has shaped the spiritual formation of a Catholic filmmaker like Scorsese and how cinema, when it seeks life in its naked truth, generates a form of spirituality.

-Cinema, often using a simple yet powerful language, has succeeded in conveying Christian values of hospitality and care for the weakest. I’m thinking of Federico Fellini’s La Strada, which was also Pope Francis’s favorite film. In which films in the history of cinema do you find these same Christian values?

Fellini’s “La Strada” -Pope Francis’s favorite film- is a foundational text: Gelsomina and the Fool are the “holy fools” of the Gospel, the little ones through whom the meaning of history passes. In that film, salvation hinges on the face of someone who counts for nothing, and this is profoundly evangelical. Throughout film history I see the same logic in many works. I’ll mention just a few, very different from one another: Roberto Rossellini’s “Open City”, where the everyday holiness of Pina and Don Pietro is born from sharing the fate of those most exposed to violence; Vittorio De Sica’s “Umberto D.”, with that elderly man who is almost invisible to the city yet becomes a living parable of dignity in poverty; Gabriel Axel’s “Babette’s Feast”, in which a free and undeserved banquet becomes an Eucharistic image of reconciliation; Clint Eastwood’s “Gran Torino”, with Walt’s final sacrifice that breaks the spiral of violence in the neighborhood. And of course many of Scorsese’s films, where grace enters “the territory of the devil,” to use Flannery O’Connor’s expression that Martin loves so much. In all these cases the language is simple and accessible, but the stakes are incredibly high: the aim is to show that a seemingly insignificant life can become a place of revelation, that welcoming the weakest is not an optional moral theme but the very center of the story.

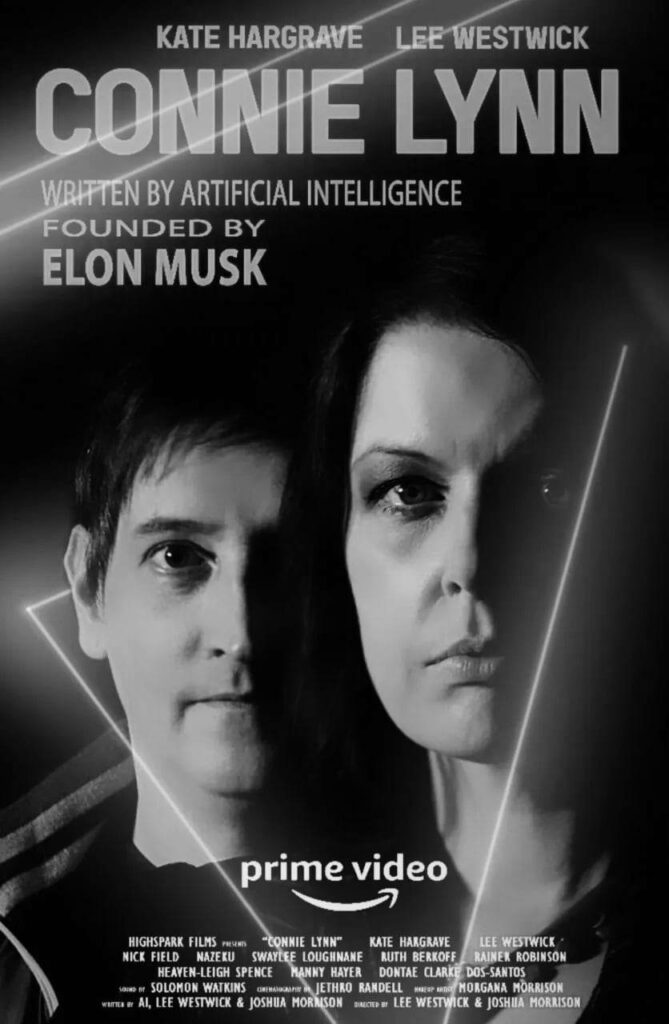

-Artificial intelligence is profoundly affecting every sector, including cinema. I’ve read that you have recently worked on the topic of Artificial Intelligence, what is your opinion of this tool?

Artificial Intelligence is not just a new technical instrument; it is becoming an environment that shapes the way we perceive the world, how we narrate it, and how we imagine it. Having worked on this subject for years, first through my reflection on “cybertheology,” and later in my writings on AI and the human person, I have tried to show that digital technologies reshape both human action and human being, and therefore directly touch matters of faith, ethics, and freedom. In cinema, we can already see some effects: algorithms that suggest what to produce and what to watch, generative systems that create images and faces, tools that promise to “replace” certain stages of writing or post-production. This opens extraordinary possibilities – new languages, new ways of accessing materials, even creative approaches to archival restoration, but it also entails serious risks: flattening the imagination onto calculated tastes, homogenizing stories, eroding the creative work of millions of professionals. For me, the decisive question is: Who is guiding whom? If AI becomes a kind of “invisible director” that determines criteria of success, timing, and faces, then industrial logic risks suffocating artistic risk. If instead it remains a tool in the hands of free and responsible authors, it can help explore new narrative dimensions, make heritage more accessible, and improve work on image and sound. But the ultimate responsibility remains human: no algorithm can replace conscience, discernment, or a living relationship with reality.

–Our magazine is dedicated to Independent Cinema, born from the production philosophy of Roger Corman’s New Hollywood and inspired as well by Martin Scorsese’s early films, such as “Mean Streets”. Today, the kind of cinema that in the United States is called “Arthouse” has less and less space to emerge in major festivals, where the economic interests of major companies and platforms prevail over the experimental spirit of young independent filmmakers, just as Martin Scorsese was in early 1970s New York. To what do you attribute this general cultural decline in the film industry, which seems to be increasingly business and less art?

I share this concern. The cinema we call independent, arthouse, or simply “research-driven” often arises from conditions similar to those of New Hollywood in the 1960s and ’70s: limited budgets, great formal freedom, and a strong connection to neighborhoods, bodies, and living languages. “Mean Streets” is a product of that world.

Today, the system of major festivals and streaming platforms is marked by a high concentration of economic power: what counts is the catalog, the brand, seriality, and audience data. The imagination risks becoming uniform because what prevails is what is easily exportable and lends itself to being replicated. Algorithms also tend to reward what “resembles” what has already been successful.

I would not speak only of “decline,” but of imbalance: cinema as an industry occupies almost all available space, while cinema as art struggles to find visibility and support. There are still festivals, theaters, film clubs, and circuits that take risks and defend research; there are foundations, schools, parishes, and universities that program challenging films and educate the gaze. But the pressure toward standardized products is evident.

In this context, the legacy of a producer like Roger Corman and of Scorsese’s early films is invaluable: it reminds us that a film can be made with very few resources, driven by a powerful inner necessity. I believe the answer is not nostalgia, but the creation of new “ecologies” of the image: networks of independent theaters, festivals truly open to risk, alliances among film schools, universities, and communities, believing or non-believing, seeking stories capable of questioning us rather than merely entertaining.

If cinema returns to “doing justice to life,” as Martin says, then even the industry will eventually have to reckon with this profound need for truth and beauty.

–

Here is the link to the book “Conversation on Faith” by Martin Scorsese and Father Antonio Spadaro: https://www.amazon.com/Conversations-Faith-Martin-Scorsese/dp/1538775387